Article

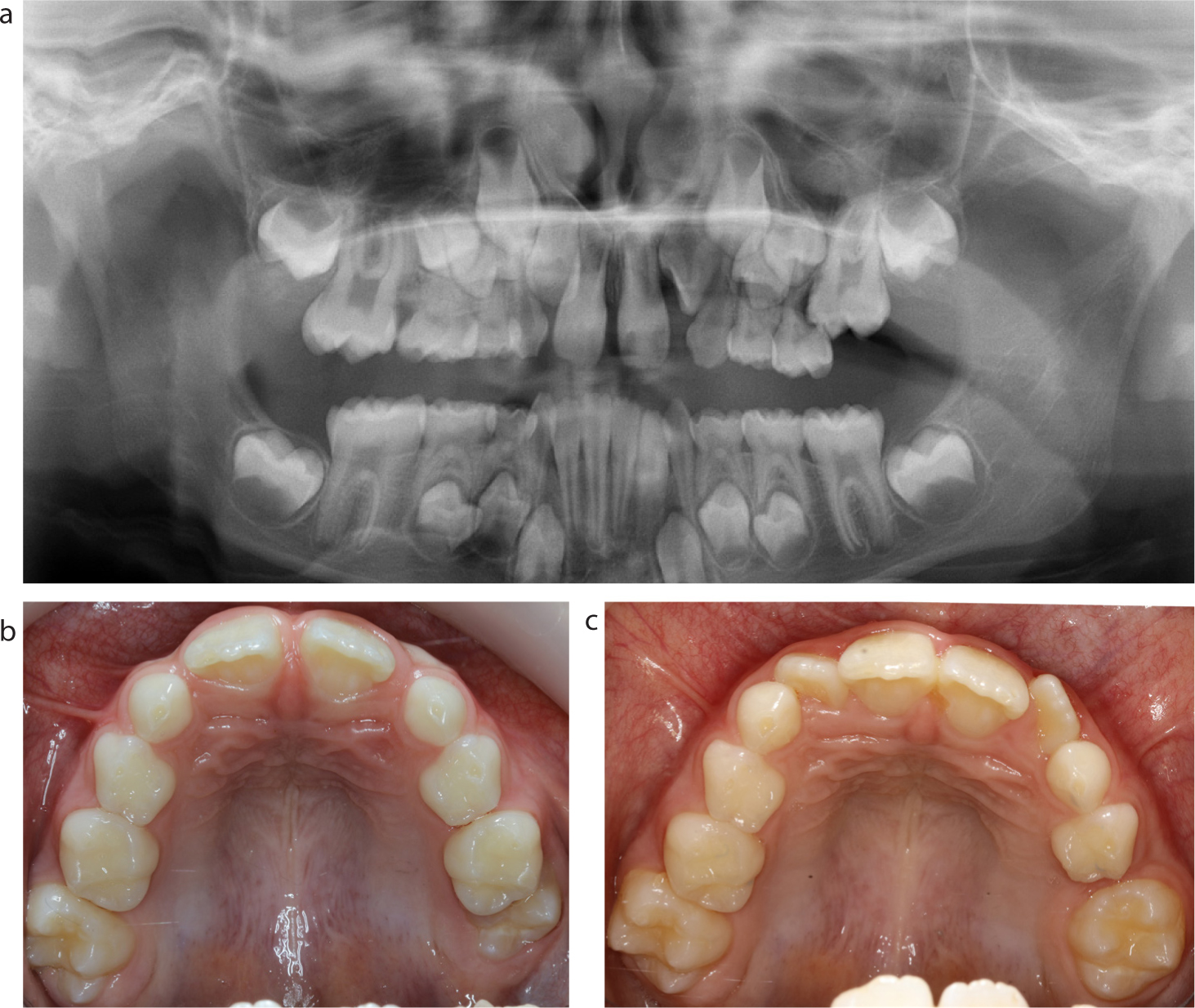

The prevalence of ectopic eruption of first permanent molars (FPMs) ranges from 0.75% to 6% in different populations, with some studies reporting a higher occurrence of impaction in the maxilla compared to the mandible.1–5 Often, the clinical presentation is of an upper FPM trapped in the convexity below the cemento-enamel junction of the primary second molar, sometimes causing resorption of the distal root of the primary tooth. In most cases, this results in a self-fulfilling preponderance of impaction because the FPM is trapped under the non-resorbable enamel shelf of the primary molar. The milder impactions may self-correct, but it has been reported that self-correction reduces after age 7 years.3 Clinicians may be tempted to extract the primary second molar, but this leads to the undesirable consequence of mesial drift of the FPM, and subsequent problems of severe crowding and the practical difficulties of distalizing the FPM (Figure 1).

The treatment aims should thus revolve around:

There are several methods that can be used to disimpact a FPM by molar distalization. The first is separation. Whether one chooses to use elastomeric or brass wire separation, there are several technical difficulties. It can be difficult to place a separator in the contact point because the FPM is trapped below the CEJ of the primary molar. Additionally, the separator in itself prevents the eruption of the FPM and it has to be removed after a week or so, with the hope that the small space created by separation is sufficient to relieve the impaction. More often than not, there is the need to replace the separator repeatedly.

Another technique involves using sectional fixed appliances. There are a variety of different approaches that have been described, including using different springs such as the Humphrey and Halterman appliance, or compressed coil spring between brackets. These appliances can be difficult to adjust in patients who are young, but moreover, this technique means that the reactive force is directed at the primary second molar, which has often already lost root length due to resorption. The result is that the tooth may be lost prematurely with the subsequent need for space maintenance.

The preferred method for resolving FPM impaction is the use of a removable appliance with a finger spring. Apart from the twin-block appliance, I almost never use removable appliances, except for this particular circumstance. The benefits are that the appliance is simple for the patient, parent and clinician to adjust, and that the reactive force is spread over the baseplate.

The design of the appliance is usually an acrylic baseplate with Adams cribs on the primary second molars, a Southend clasp on the central incisors and palatal finger spring(s) (0.6 mm SS) to distalize the FPM(s) (Figure 2). The retentive components of the appliance need to be sufficiently robust that the appliance is not dislodged when the springs are active. When the springs are activated they need to lie sufficiently distal to the buttons that have been bonded to the cusps of the FPM. Figures 3–7 show treatment of a case over 5 months using this technique.