References

The aberrant molar

From Volume 11, Issue 2, April 2018 | Pages 55-60

Article

The molar teeth are unique in that they are accessional teeth, ie they do not have a primary precursor. The eruption of the first permanent molar marks the beginning of the mixed dentition phase of development. This is the first accessional tooth to erupt and is followed by the eruption of upper and lower incisors, premolars and canines (successional teeth). The eruption of the second molar marks the establishment of the permanent dentition, which may be completed with the eruption of the third molar (if present). Abnormalities of eruption are common in the case of the third molar and less so in the case of the first and second molars.

Development of the molars

The first molar begins calcification at birth and erupts at roughly 6 years of age. As with most permanent teeth, the lower molar usually erupts just before the upper molar. The second molars begin to calcify at 3 years of age and erupt at about 12 to 14 years. The third molars may be visible radiographically between the ages of 8 to 14 years old and usually erupt between the ages of 17 to 25 years. They are the least predictable teeth in terms of their morphology and behaviour.

Third molars

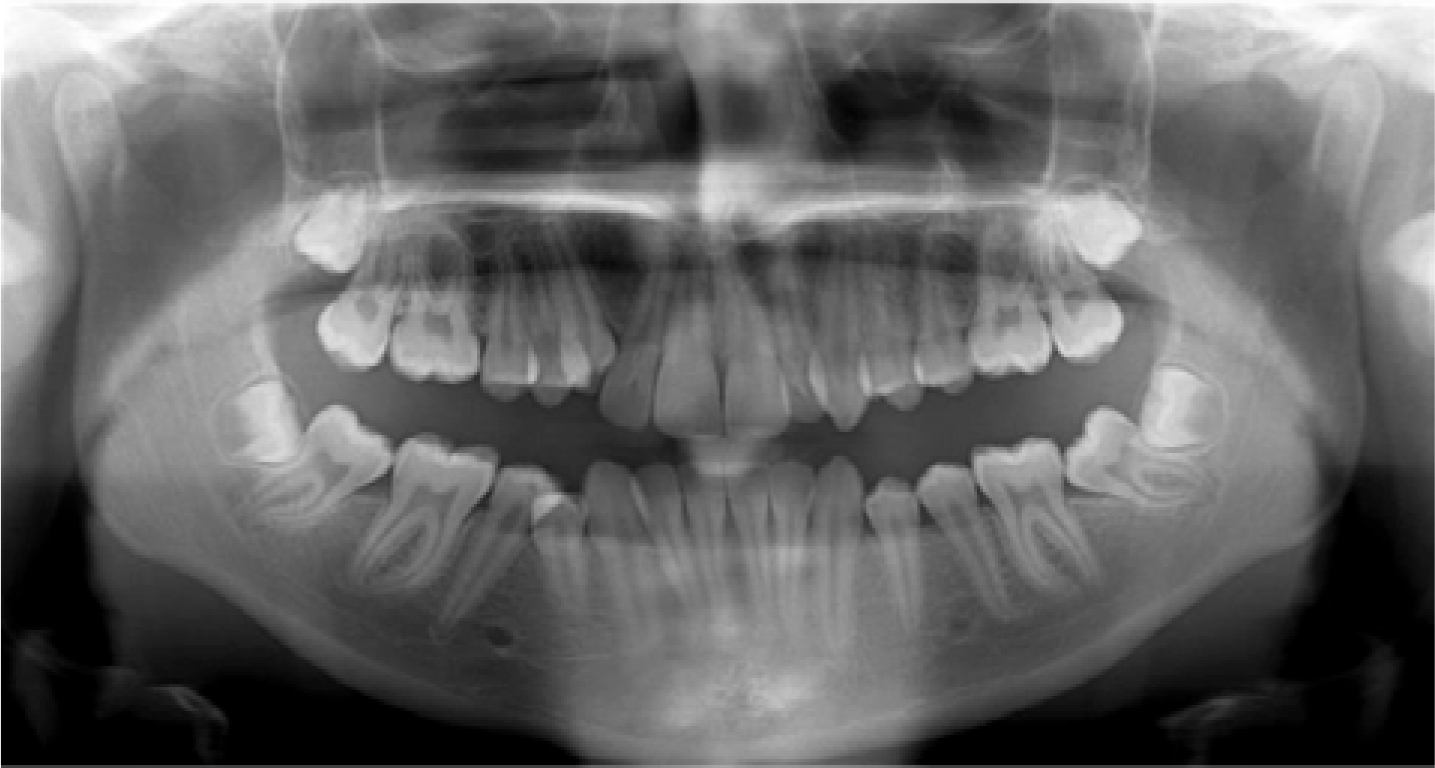

The third molars are the last teeth to develop, are the most likely to fail to develop1 (Figure 1) and the most likely to become impacted.2 The incidence of developmentally absent third molars has been reported to be between 13% and 25%.3,4 They become impacted and so may not fully erupt in approximately 20% to 30% of cases and this impaction is most frequently mesioangular5 (Figure 2).

There is no compelling evidence that the impaction of the third molar has any effect on late lower incisor crowding.6,7,8 Consequently, the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) advises that prophylactic removal of asymptomatic third molars, in order to prevent changes to incisor alignment, is not recommended.

Second molars

There is little literature relating specifically to eruptive disturbances of the second molar. The incidence of impaction of the second molar is reported as 1.5% and failure of eruption as 0.6%.9 The second molar is rarely absent, but this has been reported to occur in 0.8% to 1.5% of cases.9,10

Signs of posterior crowding

The term ‘stacked molars’ refers to the radiographic appearance of the upper molar teeth being stacked almost vertically, one on top of the other, and is indicative of posterior crowding (Figure 3). In the lower arch, posterior crowding can also be seen on a dental panoramic tomogram (DPT) and in this case the lower second molar may appear distally angulated (Figure 4). This posterior crowding is an indication that mid arch extractions may be appropriate, especially if third permanent molars are present. A distally angulated lower second molar can be problematic in the longer term, as it increases the risk of impaction of the third molar and the angulation will make restorative work more challenging.

Mesially angulated second molar

Mesial impaction of the second molar is not always evident at the beginning of treatment and often occurs when the mesial marginal ridge of the second molar gets caught on the distal aspect of the first molar (Figures 5 a−c). The second molar continues to erupt, but sometimes tips further mesially.

Treatment in the case of the mesially impacted second molar

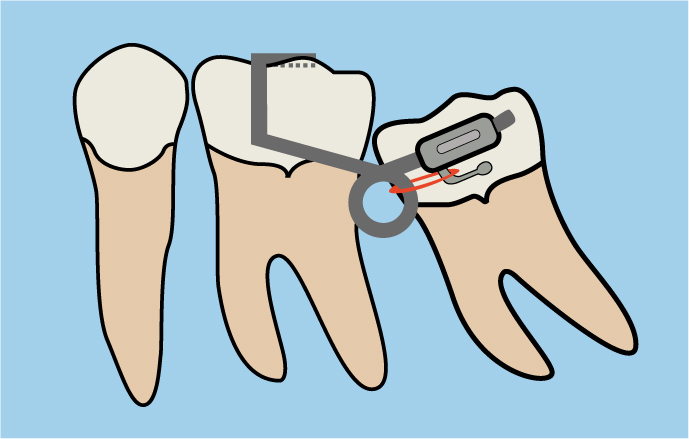

Uprighting of the second molar requires that the tooth is tipped distally. If the marginal ridge can be freed, for example with a separator, then it is possible it will self-correct. If this is not successful, or the impaction is severe, orthodontic uprighting may be required. Provided a tube can be bonded to the buccal surface of the second molar, either a continuous or a sectional archwire can be used to upright the second molar. A sectional arch10,11 can be used in combination with an existing fixed appliance or it can be used on its own. For example, a single buccal tube can be bonded onto the second molar and a sectional rectangular stainless steel wire bent such that it passes up the buccal surface of the adjacent first permanent molar and onto its occlusal surface (Figure 6). In this case, it is important that the second molar is opposed so that, as it is tipped distally by the sectional wire, the occlusion with the opposing upper arch tooth encourages the roots of the lower second molar to move mesially. Alternatively, tubes can be bonded onto both the first and second molars and a sectional rectangular nickel titanium wire used to upright the first molar (Figure 7). A lockable attachment is used to prevent the wire from slipping either mesially or distally.

Bonding a button onto the occlusal surface of the second molar and using a fixed segmental spring, or a spring on a removable appliance, will also have the effect of tipping the second molar distally, thereby disimpacting it.12

A deep impaction of the second molar may necessitate extraction of this tooth. If this is the case, then the presence and position of the third molar should be assessed (Figure 8). If extraction of the second molar occurs at or near the time of formation of the bifurcation of the third molar, there is a high likelihood that the third molar will erupt into the position of the second molar.13,14,15,16

Uprighting of the second molar is likely to become easier following any midarch extractions and space closure as the increase in available space may allow self-resolution of the impaction. If orthodontic correction is not possible and extraction is not considered a sensible option, surgical repositioning of the tooth may be required. If the procedure is performed before the completion of root formation, there is often good bony infill between the first and second molar.17,18

First molars

The first molar is one of the first permanent teeth to erupt. There is almost always sufficient space for its eruption and other factors dictate anomalies of eruption. Physical obstruction by the second primary molar is referred to as ectopic eruption and is more common in the maxilla. Occasionally, lower first permanent molars fail to erupt due to ankylosis and they are usually in intimate relation to the inferior dental canal.

Ectopic eruption of the maxillary molar

Ectopic eruption of the upper first permanent molar is a localized disturbance of eruption where the first molar comes into contact with the distal aspect of the second deciduous molar. This occurs in roughly 4% of all orthodontic patients,19 with a higher incidence reported in siblings.20 There is often resorption of the distal aspect of the second deciduous molar, in which case only the distal portion of the first molar crown is visible intra-orally (Figure 9). If resorption of the second deciduous molar is extensive, it can lead to a direct communication between the mouth and the dental pulp (Figure 10), resulting in symptoms including pain, which will inevitably necessitate extraction of the second deciduous molar.

Treatment in the case of the ectopic maxillary first molar

Two-thirds of ectopic first molars impacted against the distal of the second deciduous molar will spontaneously self-correct.21,22 Placement of a separator to free the mesial portion of the first molar will often encourage disimpaction of the tooth. However, access is notoriously difficult and separator placement can be uncomfortable. Removal of the deciduous tooth will allow the first molar to erupt, but the inevitable consequence is space loss and future crowding in the premolar regions as the molar moves further mesially (Figure 11).

Single ankylosed mandibular first molar

Very occasionally, the lower first permanent molar becomes ankylosed and can be seen in close relationship with the inferior alveolar nerve and canal. Fortunately, it is a rare occurrence, with an incidence of only 0.05%.23 The aetiology is unclear, but it may be a variation of primary failure of eruption, associated with cystic change within the follicle or the presence of odontomes.24 A local abnormality in bone resorption overlying the first molar on one quadrant is unusual, but possible.25 Should the second molar erupt before the first molar, space loss and tipping will result in physical obstruction of the first molar (Figure 12). If root formation has progressed, and there is intimate relation with the lower border of the mandible, then the roots may splay mesially or distally, appearing dilacerated.

Treatment in the case of the ankylosed mandibular first molar

Although thankfully rare, ankylosis of the mandibular molar can represent a considerable treatment challenge. If there is any physical barrier to eruption, removal of the obstruction should allow either spontaneous or orthodontically assisted eruption. Surgical luxation of the tooth and orthodontic extrusion may be suitable if the root morphology is favourable.25 In other cases, extraction or coronectomy is the treatment of choice, as attempted orthodontic extrusion may result in unwanted intrusion of the adjacent teeth, possibly creating a posterior open bite.

Primary failure of eruption

The term primary failure of eruption (PFE) is used to refer to cases where there is failure of eruption of all teeth distal to the most mesially affected tooth.26,27,28Figure 13 illustrates such a case where the teeth distal to the canines have failed to continue to erupt and make occlusal contact with their counterparts in the opposing arch. PFE may be an autosomal dominant inherited trait and there is evidence that mutation of the PTH1R gene is responsible.27,28,29 Treatment of PFE is extremely difficult and, even though teeth may appear responsive to orthodontic force shortly following surgical uncovering, they invariably become ankylosed. Dentoalveolar osteotomy is the only method of repositioning the tooth or teeth.

Conclusion

This article has reviewed and summarized the aetiology and treatment options for eruption disturbances of permanent molar teeth. With the exception of the third molar, posterior teeth often erupt without incident, but there are instances where this is not the case, as outlined. Early identification of these eruption disturbances may simplify treatment.