References

Managing the adenomatous odontogenic tumour (AOT): a case series

From Volume 10, Issue 4, October 2017 | Pages 132-138

Article

The adenomatoid odontogenic tumour (AOT) is an uncommon benign tumour, originally described by Steensland in 1905,1 although it was not recognized as an odontogenic neoplasm until 1948.2 A variety of terms have been used to describe this tumour:3

The World Health Organization histological typing of odontogenic tumours has described the AOT as follows: ‘A tumour of odontogenic epithelium with duct-like structures with varying degrees of change in the connective tissue. The tumour may be partly cystic and in some cases a solid lesion may be present only as masses in the wall of a large cyst. It is believed that the lesion in not a true neoplasm’.4

The frequency of AOT accounts for approximately 2.9−6.8% of all odontogenic tumours.4 This tumour ranks fifth among odontogenic tumours in the oro-maxillofacial region.2

Although the age range of patients affected with AOT is between 3−82 years, two thirds of the tumours are diagnosed in the second decade of life, with more than half of the cases found between the ages of 13−19 years.5 Orthodontists often assess and treat teenage patients: therefore they must be aware of this possible diagnosis in the aetiology of the delayed eruption of the permanent canine.

The English literature reports a female to male ratio for all age groups is 2.3:1.1 Adenomatous odontogenic tumours have been described in all races, with a particular preponderance amongst black Africans: AOT has a prevalence of 1.2% in Caucasians and 9% in black African patients.6

Classification of AOT

The AOT has been described as occurring both intra-osseously and extra-osseously.6 The AOT appears in three clinical variants:

Radiographically, the intra-osseous variants comprise both a follicular and an extra-follicular type.4

Follicular and extra-follicular variants

Follicular and extra-follicular variants:

A large review highlighted the teeth involved with this tumour and reflected the findings reported in the literature (Table 1).

| Teeth | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | C | D | Not described |

| Maxillary | 2 | 16 | 29 | 9 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Mandibular | 2 | 7 | 18 | 7 | 3 | 3 |

Peripheral variant

A peripheral variant:

The management of three clinical cases are highlighted, when the patients presented with impacted upper and lower permanent canines and therefore required a multidisciplinary approach involving both the orthodontic and the oral and maxillofacial teams.

Case reports

Case 1

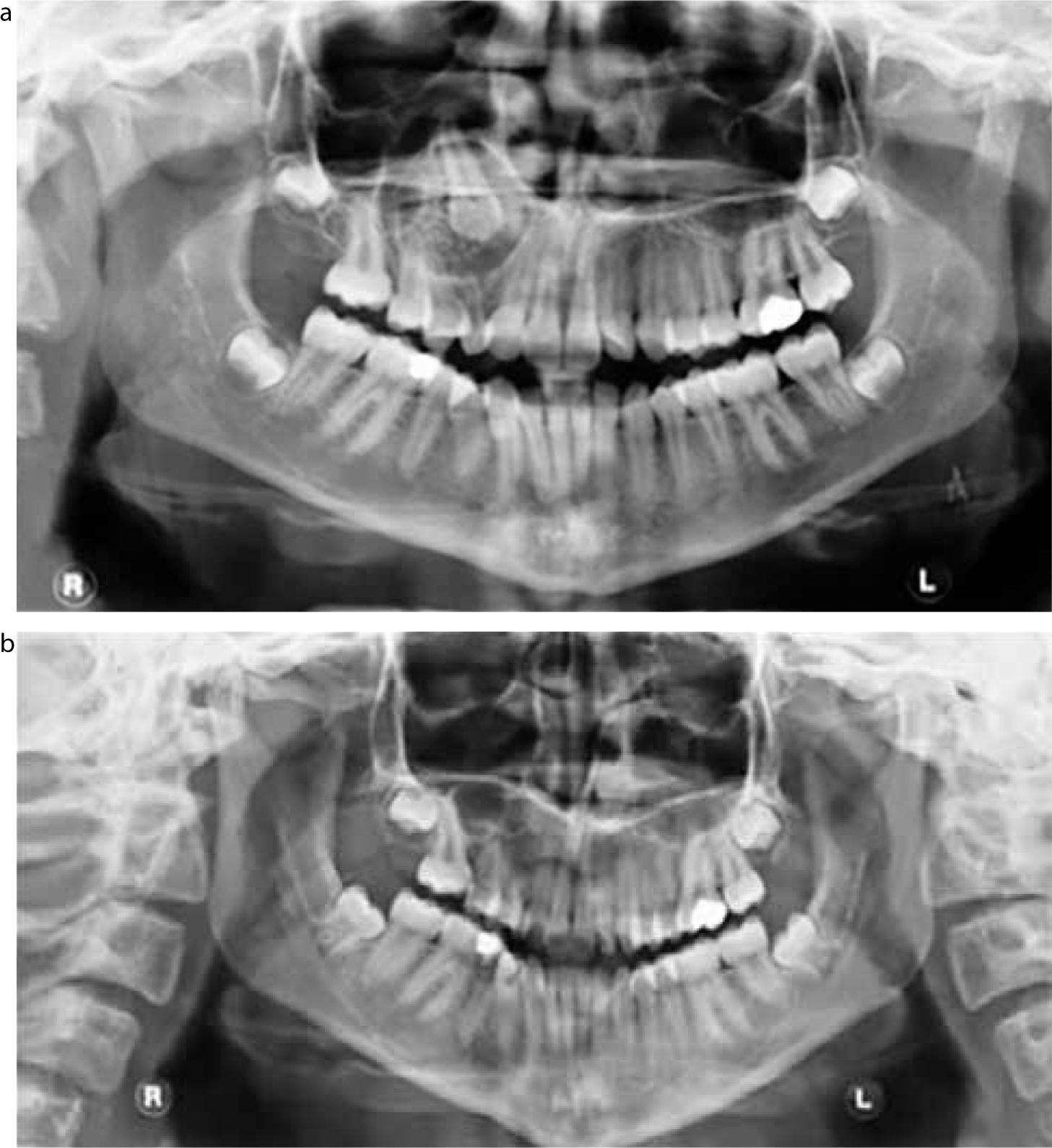

An Asian female, aged 12 years and 9 months, was originally referred to the orthodontic department regarding the management of her poor quality first permanent molars. An OPG radiograph taken in 2006 (Figure 1) revealed generalized delayed dental development with unerupted premolars and upper permanent canines. The upper right canine had a slightly enlarged follicle surrounding the crown of the tooth. Following management of the poor prognosis first permanent molars, she was subsequently discharged.

She was re-referred back to the same department in 2009 and seen by another clinician, where she presented with a Class I malocclusion on a mild skeletal III base in the permanent dentition with a retained upper right primary canine and unerupted upper right permanent canine. The upper right first permanent molar had been extracted and the upper left first permanent molar was heavily restored. The upper right canine was not palpable and there was clinical evidence of a buccal plate expansion in that region (Figure 2).

Special investigations

The orthopantogram taken in 2009 (Figure 3) demonstrated a well-defined unilocular radiolucency with evidence of small radio-opaque foci. The lesion encapsulated the crown of the UR3 and three quarters of the length of the root extending up to the floor of the maxillary antrum. The lesion had enlarged by 17 mm between 2006 and 2009, demonstrating a slow growth rate, with concomitant deflection of the adjacent roots of the lateral incisor and premolars. There was minimal root resorption associated with the URC.

Management

The URC was retained and the UR3 was removed as deemed as poor long–term prognosis. A mucoperiosteal flap was raised to expose the unerupted maxillary canine and the tumour was enucleated under general anaesthetic (Figure 4). Histological sections of the cyst lesion revealed features of an AOT, consistent with those associated with the follicular variant of the tumour. This included a characteristic, well-defined unilocular radiolucency often associated with the crown and root of an impacted maxillary permanent canine (Figures 3 and 5)

Case 2

A 13-year-old Caucasian/Filipino female presented following referral from a specialist orthodontic practice regarding ‘looseness of upper right baby tooth’. Clinically, the upper right primary canine was grade II mobile with a buccal swelling in the upper right canine region with concomitant extrusion of the UR1 and UR2 (Figure 6) and mesial angulation of the upper right first and second premolars.

Special investigations

The OPT confirmed the presence of a unilocular radiolucency encapsulating the root and crown of the upper right canine tooth with deflection of the adjacent dental roots. There was minimal resorption associated with the retained primary canine.

Management

A diagnosis of a dental follicular cyst was suspected and traction attempted. The upper right canine failed to erupt and required surgical removal. Treatment involved extraction of the retained upper right primary canine and enucleation of the lesion. The canine was mobile and had minimal bony support.

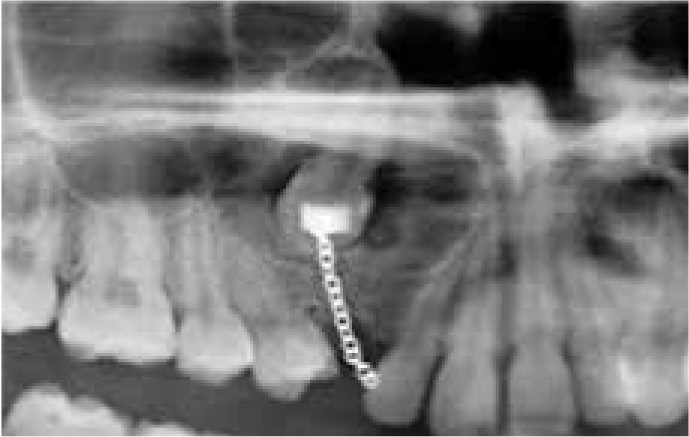

The histopathological report confirmed the follicular variant of an adenomatous odontogenic tumour. A 4-month time period was allowed for spontaneous resolution of the cyst cavity and bony infill, prior to orthodontic traction. The permanent canine was left in situ at the time of surgery, despite its increased mobility. The tooth ended up requiring removal (Figure 7).

Case 3

A 29-year-old Afro-Caribbean female was referred to the oral and maxillofacial department presenting with a lesion on the left side of the mandible in the premolar region. An OPT demonstrated a unilocular swelling with well demarcated borders (Figure 8).

Management

The tumour was enucleated under GA and the histology confirmed the diagnosis of an AOT (Figure 9). Unfortunately, the patient did not return for a follow-up appointment and was subsequently discharged.

Discussion

These cases are characteristic of those described in the literature. A common finding in all three cases was the painless, yet slow growing nature of the lesion.⁸ Two cases were described in the maxilla with one in the mandible. This is consistent with the literature as these lesions are predominately found in the maxilla (maxilla to mandible 2.1:1),3,4 with the presence in the anterior maxilla accounting for over half of the cases of the intra-osseous variant.

Two out of the three cases presented here were associated with the crown of the embedded tooth and therefore described as follicular variants. The third case described the lesion in the mandible and can be classified as an extrafollicular variant, demonstrated by its lack of association with any part of the adjacent teeth. The well-defined unilocular radiolucency is often found between, above or superimposed upon the roots of erupted permanent teeth, making diagnosis difficult. These variants commonly cause displacement of neighbouring teeth (Figure 8), however, root resorption is rare. They are also commonly found in the mandible, particularly in black African populations.4

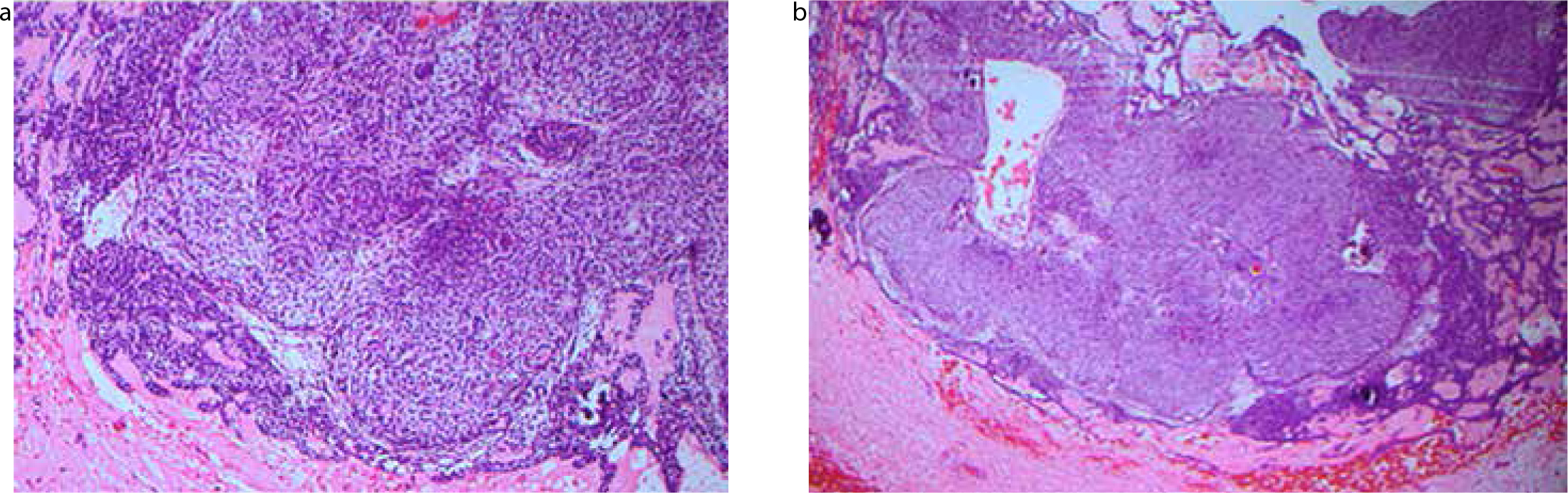

All variants of AOT demonstrate a similar histology, containing areas of microcalcification, most likely pre-enamel.9 The histology reports on the cases confirmed were consistent with features of an AOT with a mixture of cellular and glandular tissue interspersed with calcific material. The intra-osseous follicular AOT frequently resemble the dentigerous cyst. A hallmark feature of AOTs is that they often encapsulate the entire tooth, whereas the dentigerous cyst usually encapsulates the crown only. The final diagnosis should be made on the basis of a thorough histological examination.10

Radiographic findings

Radiographic findings in the present cases are consistent with those described in the literature for the intra-osseous variants. For two-thirds of the intrabony lesions, the radiolucency shows a pattern of scattered radio-opacities. Intra-oral periapical radiographs are superior to panoramic radiographs in detecting these calcified deposits, although have the obvious disadvantage of being incapable of capturing impacted teeth located high in the maxilla. The increasing role of CBCT may have an advantage in diagnosis and management.

Careful examination of the follicular variants described in our cases help distinguish this lesion from other possible lesions. Most AOTs occur intra-osseously and the surrounding crowns are attached to the necks of the teeth in a true follicular relationship. This was evident in Cases 1 and 2 where the AOT not only encapsulated the crown but a considerable portion of the root. This is consistent with what has been described in the literature when establishing a definitive diagnosis based on special investigations.4 A study conducted in Japan undertook a survey of 126 cases and, interestingly, their findings demonstrated a huge variation in the pre-operative diagnosis for the AOT (Table 2).

| Pre-operative Diagnosis | No. Of cases |

|---|---|

| Dentigerous cyst | 41 |

| Adenomatoid odontogenic tumour | 8 |

| Calcifying odontogenic cyst | 7 |

| Benign tumour | 7 |

| Odontogenic tumour | 6 |

| Intraosseous cyst | 4 |

| Odontogenic cyst | 3 |

| Globulo-maxillary cyst | 3 |

| Ameloblastoma | 2 |

| Odontoma | 2 |

| Residual cyst | 2 |

| Epulis | 2 |

| Tumour | 1 |

| Haemangioma | 1 |

| Pleomorphic adenoma | 1 |

| Odontogenic tumour or cyst | 1 |

| Fibrous dysplasia | 1 |

| Total | 92 |

| Not described | 34 |

Histopathology

Histological examination reveals that all AOT variants share similar microscopic characteristics, confirming their common embryonic origins.6,11,12 However, the origin of the extrafollicular variant remains less clear.6 The extrafollicular variant in our case clearly demonstrated typical features characteristic of this lesion, including an organized arrangement of both dark and light cells, with larger cells interspersed with duct-like structures. There were components of small dark cells and larger cells arranged with scattered glandular lumina. Some of the glands contain central rounded acellular masses, most likely representing pre-enamel. There was no evidence of nuclear pleomorphism mitoses or necrosis.

Reports from Case 1 and 2 confirmed similar histological findings, with the lesion being described as composing sheets and islands of odontogenic epithelium forming duct-like structures interspersed with microcalcifications (Figure 10).

Pathological findings

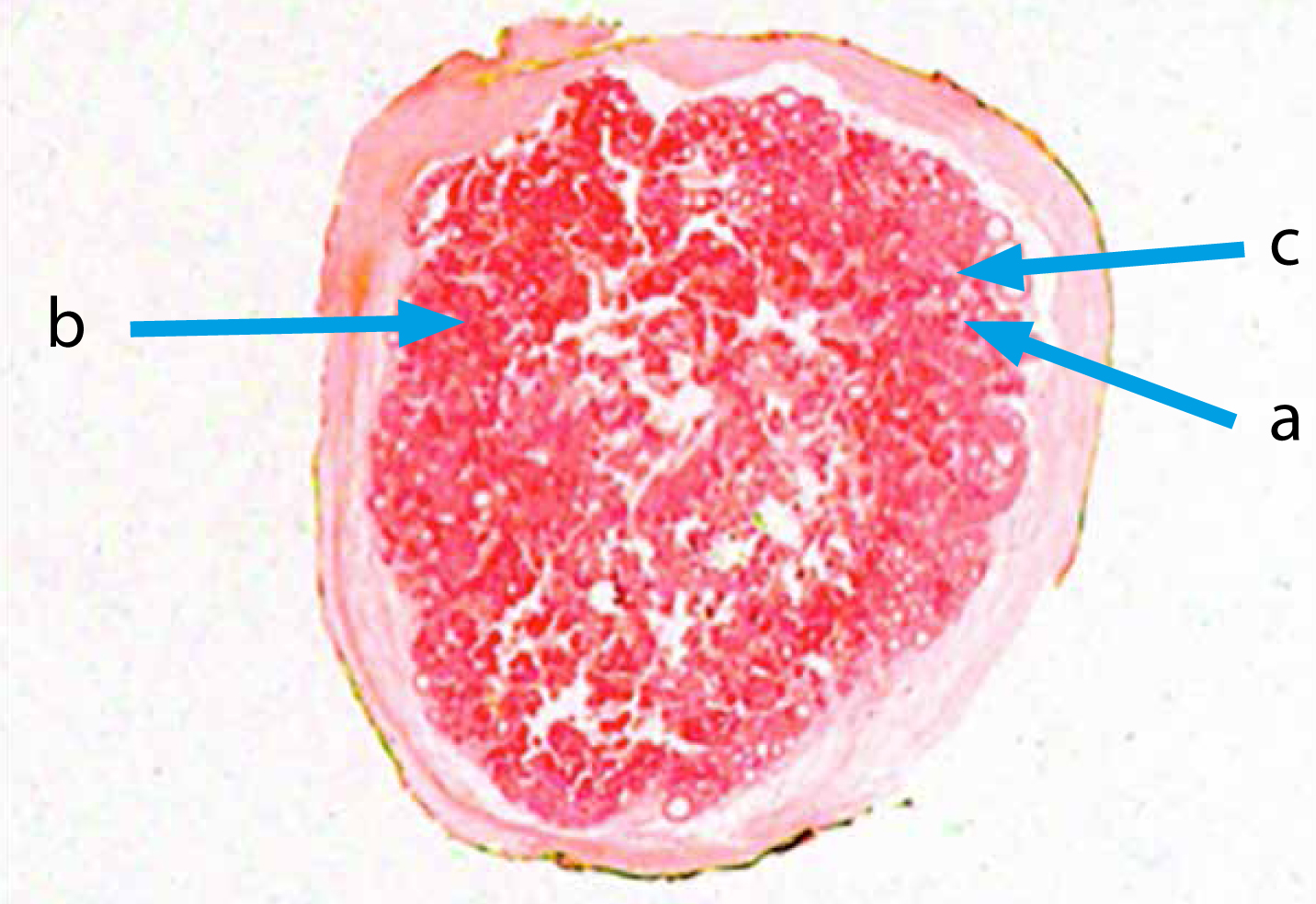

Following surgical excision of the tumour, the lesions removed from Case 1 and 3 were intact and measured similar dimensions, nearly 3 cm wide and 2 cm in depth, with a pale-coloured exudate with the contents described as ‘cheese-like’. However, Case 1 contained calcification type exudate. These calcified deposits, which have been considered to be a form of enamel cementum or dentine cementum, are seen in approximately 78% of AOTs and can be used to assist in the process of diagnosis.

Conclusion

Management often involves a multidisciplinary approach and, given the age range of the patients, there are invariably orthodontic implications due to the association with unerupted teeth.

All three cases were managed with enucleation, with the literature suggesting that, given that the majority of AOT cases present as a well encapsulated growth, treatment should indeed involve a conservative surgical approach with curettage or surgical enucleation.3,13,14 A review of two case reports in Japan has highlighted the different management of the lesion associated with unerupted teeth. Two cases involving the intra-osseous follicular lesion were managed differently, with one resulting in enucleation and removal of the associated tooth and the other being managed with the preservation of the impacted tooth followed by an orthodontic appliance.

There are no clinical guidelines on the management of these lesions and a decision must be made in theatre to assess the long-term prognosis of the affected tooth. Sato et al reported on the benign nature and similar histology associated with all three variants of AOT and it would seem reasonable that treatment modalities should be quite similar for each.10

Furthermore, good success rates have been achieved with these approaches, where the rate of recurrence is reported as negligible,3,7 although radiographic follow-up can be considered, as in Case 1.