Abstract

This article reports on a case presenting to a university dental hospital. We encourage readers to assess and develop their own management plan. Potential options and the treatment carried out are discussed.

From Volume 14, Issue 4, October 2021 | Pages 223-227

This article reports on a case presenting to a university dental hospital. We encourage readers to assess and develop their own management plan. Potential options and the treatment carried out are discussed.

This article reports on a case presenting to a university dental hospital. We encourage readers to assess and develop their own management plan, but we discuss potential options and the treatment carried out.

The patient was referred by a specialist orthodontist regarding concerns relating to developmentally absent maxillary lateral incisors and an impacted lower left second premolar (LL5). The patient disliked the spaces between her upper teeth and was aware of a ‘stuck’ tooth. She was medically fit and well, and there was no relevant dental history.

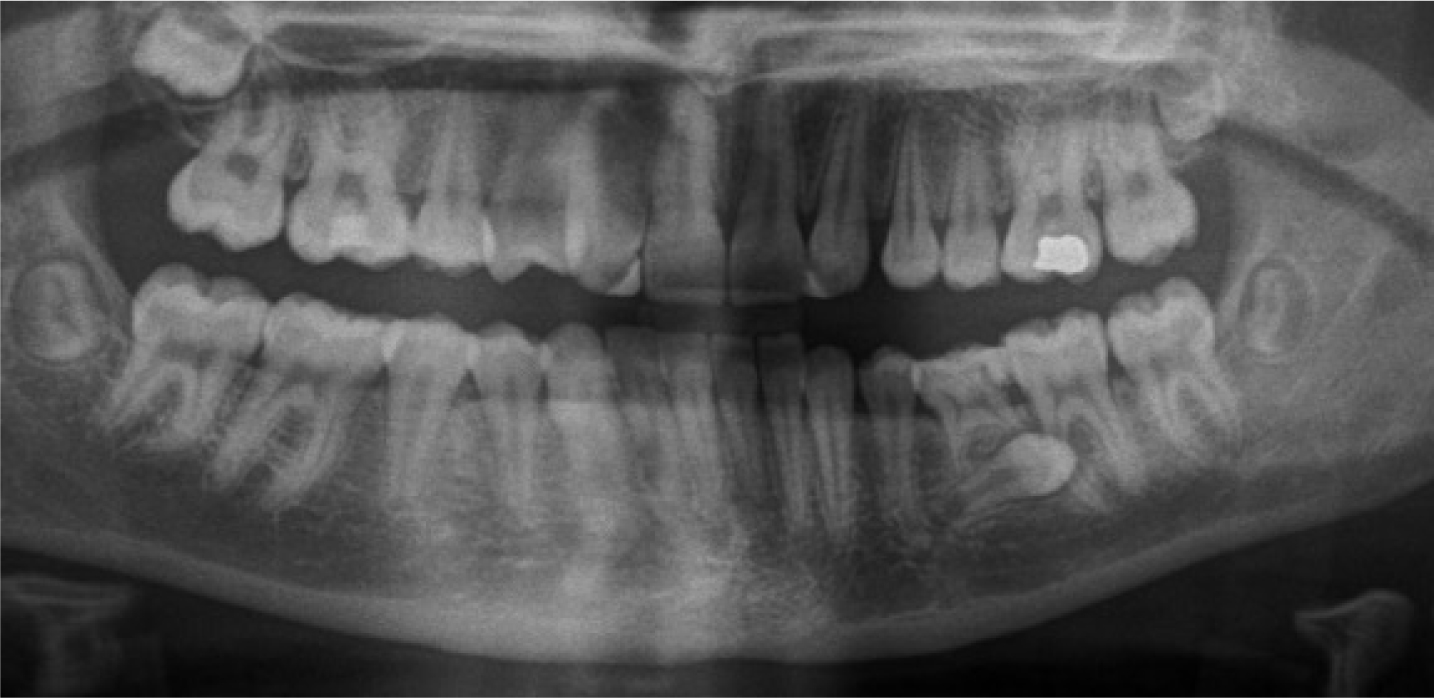

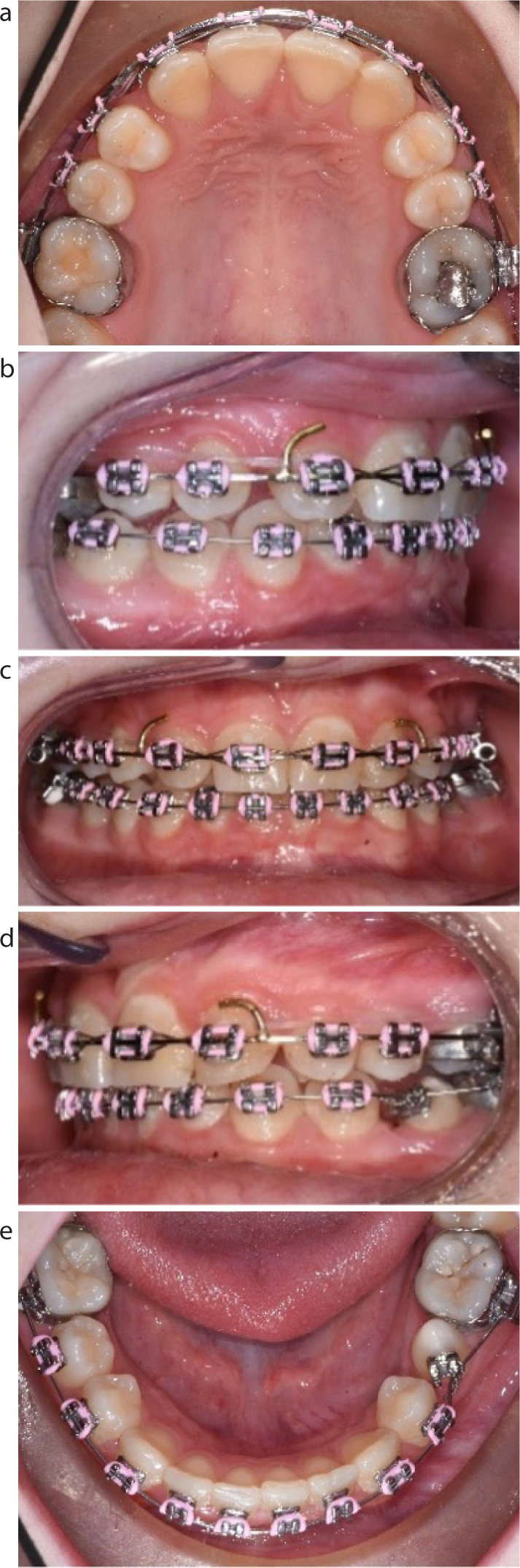

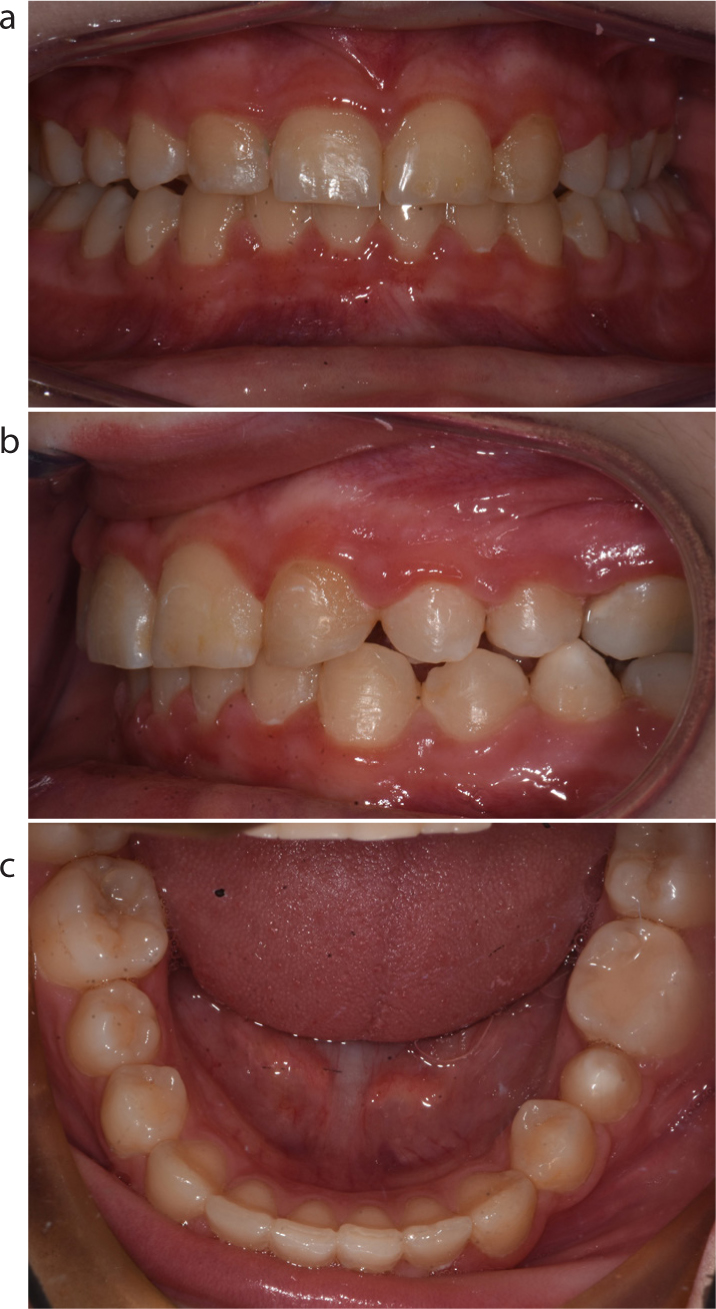

The patient was 12 years old and she presented with a Class I malocclusion on a skeletal I pattern with average vertical proportions. The malocclusion was complicated by hypodontia of UR2 and UL2, carious retained LLE and delayed development and horizontal lingually impacted LL5 (Figure 1).

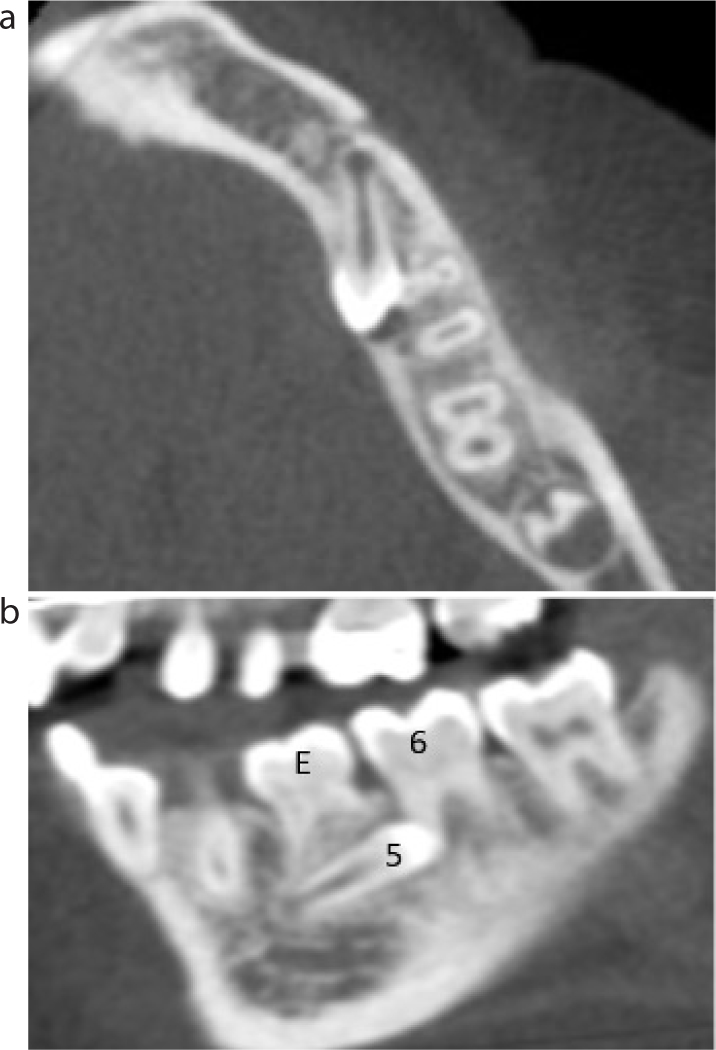

An orthopantomogram (OPG) confirmed absence of the maxillary lateral incisors (Figure 2). The LL5 appeared diminutive with reduced root formation. The crown was lying horizontally, and pointing distally. There appeared to be no evidence of root resorption on the LLE; however, there was a radiolucency associated with its relation to LL6, suggesting possible mesial root resorption. A CBCT was taken to facilitate orthodontic and surgical treatment planning. Axial and sagittal views of the CBCT are shown in Figure 3. The CBCT report is summarized as follows:

We encourage readers to analyse the presented case and develop their own treatment options and preferential plan along with mechanics for the proposed treatment. The treatment provided, and a discussion of the options is now presented.

Considering the missing lateral incisors with a Class I incisor relationship, minimal upper arch spacing and full II molar relationship, it was decided to accept the position of the maxillary canines and camouflage them as lateral incisors. They were favourable for camouflage based on their slightly diminutive size, light colouration and lower gingival margin. These options were discussed in combination with orthodontic and restorative specialists. Camouflaging involved discing of the canine tip and direct composite build-up of a mesio-incisal edge to improve the coronal morphology.1,2 The patient was satisfied with the outcome and only requested ‘closing the spaces’ remaining in the upper arch. The canines were a good colour match; however, should the patient have wished to ‘lighten’ the shade, then selective tooth bleaching could have been considered.

Theoretically, an alternative option was to ‘open space’; however, this would have required removal of the first premolars or the compromised first permanent molars, with anchorage re-inforcement, both followed by extensive orthodontic treatment to distalize the canines. There would then have been a restorative burden for the patient to maintain the two prostheses that would most likely have taken the form of a resin-retained bridge initially, although implants could have been considered following cessation of growth. There is evidence to suggest that space closure maybe preferable to space opening for better periodontal health and perceived aesthetics.3,4

Following the radiographic investigations of the LL5 and LL6, the patient was given the following options regarding ongoing treatment.

The LLE could be maintained for as long as possible; however, its prognosis was poor based on the infra-occlusion, short root morphology and disto-occlusal restoration with secondary caries into the pulp chamber.5 The LLE would require root canal therapy and subsequent restoration to be maintained for as long as possible.

Leaving the LL5 in situ may have resulted in root resorption of the LL6 or cyst formation, or it may have continued to migrate and potentially erupt lingually; however, this behaviour was difficult to predict. There are no good data to report the incidence of cystic change of unerupted teeth, although it is believed to be around 1%.6 Root resorption of adjacent teeth is most commonly associated with ectopic maxillary canines and is reported to be as high as 67% when assessed using CBCT.7

Upper fixed appliances could have closed the upper arch spacing and helped to further camouflage the canines as lateral incisors and the first premolars as canines; however, to maintain closure of the spacing, indefinite retention would be required.

Based on the poor long-term prognosis of the LLE and the unfavourable position of the LL5, they could both have been extracted, eliminating potential future complications. The subsequent space could then be restored with a removable/fixed prosthesis should it have been requested; however, a restorative burden would then exist, requiring life-long care and maintenance. Leaving the space could result in overeruption of the opposing UL5.

The surgical procedure to remove the LL5 risks damage to the adjacent dentition and floor of mouth, or to the inferior alveolar nerve owing to its close proximity. The incidence of nerve injury associated with surgery to impacted mandibular premolars is not well reported, but is assumed to be low; however, based on the proximity of the adjacent structures, procedures in this region should be consented for permanent nerve injury.

This would help to address the patient's concerns about spacing in the upper arch. Furthermore, appliances could reduce the size of the spacing in the LLQ to improve the stability of any potential prosthesis, as well as reduce the risk of opposing UL5 overeruption.

The LLE was considered to have a poor prognosis and its removal would have provided enough space for alignment of the LL5. The position of the LL5 was unlikely to improve by itself and, therefore, exposure and traction would be required to align it. This surgical procedure caries the risk of nerve injury or damage to adjacent tooth, albeit, a lower risk than removal of the tooth. Furthermore, the LL5 may have been ankylosed, in which case, alignment would not have been possible; however, based on the continued migration of the premolar, ankylosis was unlikely. There is an increased risk of root resorption to the mesial roots of the first permanent molar when uprighting the LL5. This plan did carry an increased orthodontic burden, the outcome of which was unpredictable and LL5 could still have required extraction and prosthetic replacement at a later date.

The evidence for predicting nerve injury or success in alignment of these cases is difficult to quantify for patients based on limited high-quality evidence. There are, however, many case reports of successful similar treatments to align impacted mandibular premolars.8–11.

Following full discussion with the patient and her parents regarding the treatment options, the patient wanted to attempt alignment of the LL5 using fixed appliances because she was keen to avoid any gaps or the need for false teeth. She was also concerned about the spacing in the upper arch, despite camouflaging the canines as lateral incisors.

Owing to the pre-treatment upper arch spacing and rotation of the canines, there was a higher risk of relapse and indefinite use of a vacuum-formed retainer, combined with a bonded retainer, was recommended. In the lower arch, a vacuum-formed retainer should maintain satisfactory alignment of the labial segment.

The above case has benefited from the close working of specialist orthodontists with restorative and oral surgery specialists. In the upper arch, restorative colleagues camouflaged the canines as lateral incisors and a reasonable aesthetic outcome was achieved without the need for orthodontic treatment; however, owing to the patient's concerns regarding the spacing, upper fixed appliances were used ito improve alignment and close the spacing.

In the lower arch, it was the parent's preference to remove both the LLE and LL5 and plan for a prosthesis in the resulting space. This was driven by the parent's satisfaction with the alignment of the dentition, as well as concerns over the implications of time and commitment for potentially long orthodontic treatment. Restorative input was beneficial in discussing the long-term implications for each of the restorative options. The patient, on the other hand, was not keen on the prospect of a ‘false tooth’ nor its indefinite maintenance and wanted to at least attempt alignment of the LL5 in the first instance. The patient and her parents were happy to accept the unpredictable nature of this treatment and risk of root resorption to the currently healthy LL6. This conflict of opinions required careful discussion among all stakeholders to ensure informed consent was achieved, and all parties were satisfied with the plan.

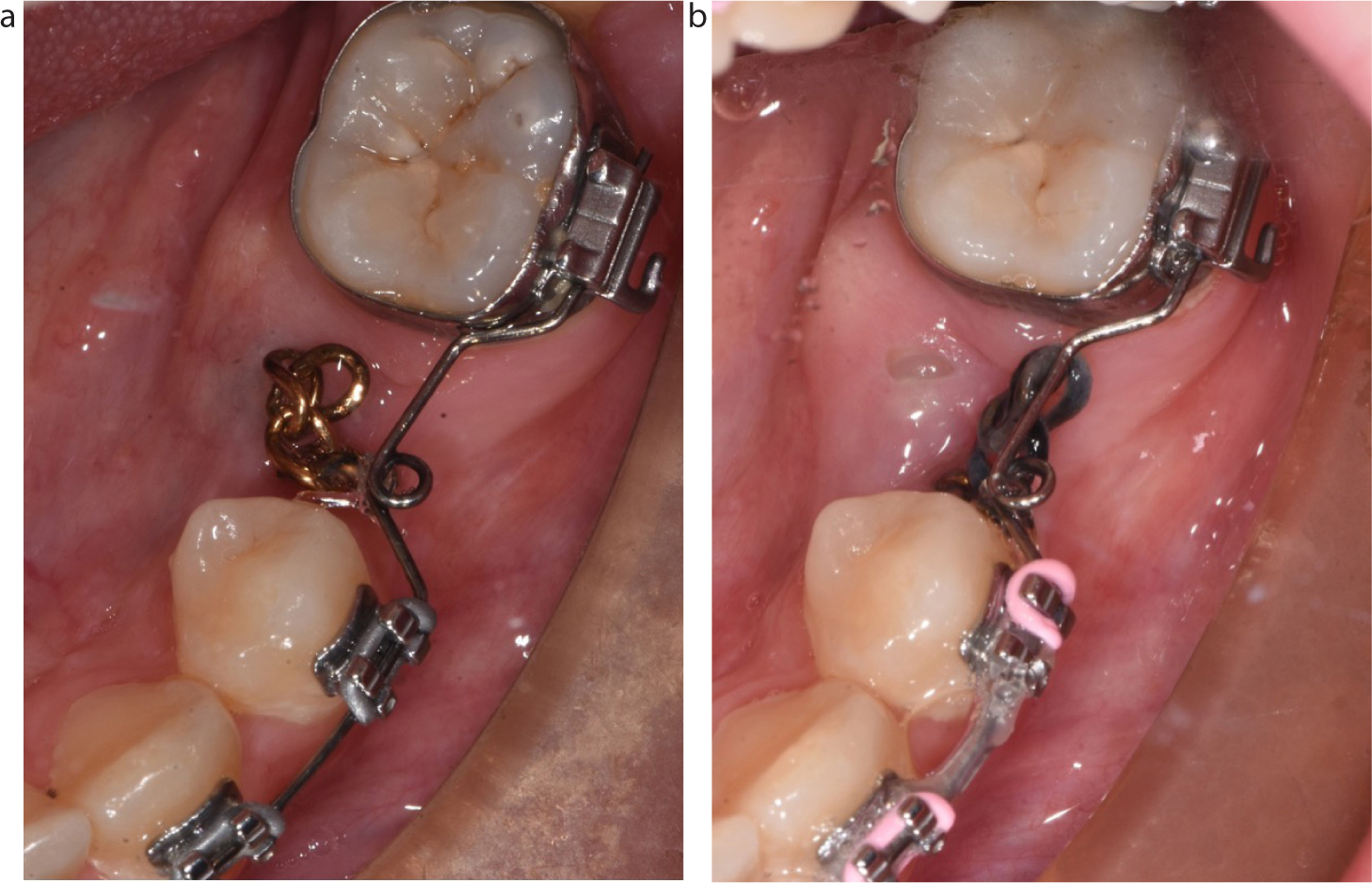

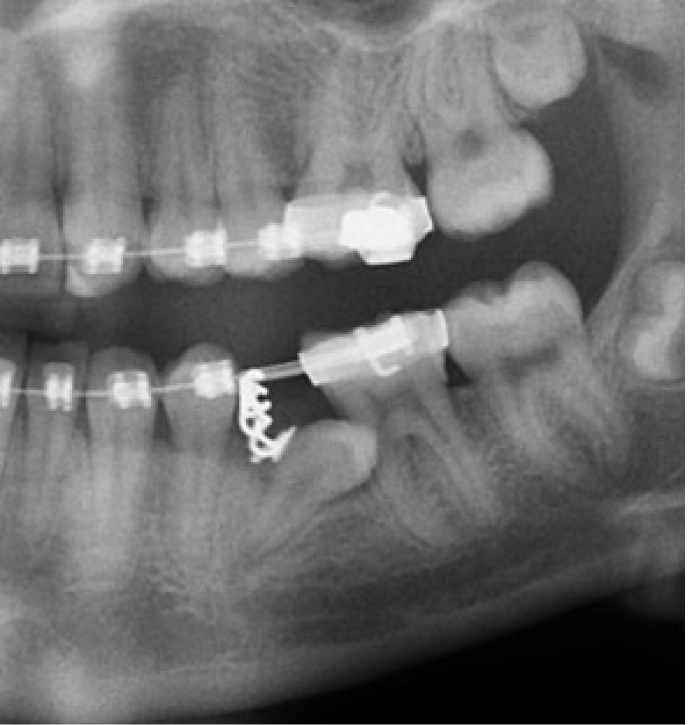

Close liaison with oral surgery colleagues along with the use of CBCT was essential in surgical planning. It was key to communicate the ideal location for bonding the gold chain. This was on the mesial aspect of the LL5, as close to the cemento-enamel junction as possible. This facilitated traction with a mesial and vertical vector to upright the distally impacted LL5. Careful mechanics were employed to reduce the chance of dragging dental surfaces against each other as the LL5 uprighted. Periodic radiographic review was undertaken in order to check on progress of the alignment of the LL5, as well as for checking for signs of significant root resorption of the LL6.

The coronal morphology of the LL5 was less than ideal. With the benefit of hindsight, and review of the CBCT images, the abnormal coronal morphology could have been noted. The implications for this were acceptance both of a diminutive crown with less than ideal contact points with adjacent teeth, which may result in food packing, and inclusion of a tooth-size discrepancy affecting the final occlusal fit. Alternatively, the LL5 could have been built up, directly or indirectly, to provide a more normal morphology in keeping with that of a premolar. This would facilitate an ideal occlusal fit. This would carry a restorative burden that the patient was originally keen to avoid. The greatest coronal width of the LL5 is 6 mm, slightly less than the 7 mm LL4; therefore, aligning the LL5 in along this plane would have the least impact on any tooth size discrepancy. The patient is currently considering her restorative options for the LL5 and to date the patient has not requested any further restorative treatment.

A case has been presented that shows orthodontic management in combination with restorative and oral surgery management of a patient who presented with developmentally absent maxillary lateral incisors and an impacted mandibular premolar. The case highlights the importance of shared decision-making among all stakeholders.