References

Dental Implications of Pycnodysostosis: A Case Series

From Volume 11, Issue 1, January 2018 | Pages 21-24

Article

Pycnodysostosis is a rare skeletal disorder that was first reported and characterized by Maroteaux and Lamy in 1962,1 but it does appear in the literature prior to this under various descriptions.2 It is an autosomal recessive genetic condition with an estimated incidence of 1.7 per 1 million births3 and is caused by a mutation in the gene for cathepsin K (CTSK), mapped to chromosome 1q21.4 CTSK is a lysosomal enzyme which is well expressed in osteoclasts and is responsible for the breakdown of proteins in the bone matrix.5 Defective tissue-specific expression of this enzyme causes a decrease in bone turnover and therefore osteosclerosis. Increased bone density and fragility paired with reduced vascularity are responsible for many of the clinical manifestations of pycnodysostosis.6

Pycnodysostosis is characterized by short stature, increased bone density and fragility, cranial abnormalities with delayed closure of sutures, acro-osteolysis of the distal phalanges and clavicular dysplasia.4,6,7,8 There are several maxillofacial features reported, including:

The oral and dental findings include:

Pycnodysostosis is primarily diagnosed on the basis of clinical and radiographic presentation, however, it is now common to carry out genetic testing to confirm diagnosis.11 Pycnodysostosis is usually diagnosed at an early age as children present with proportionate dwarfism and open anterior fontanelles. Occasionally, diagnosis can be missed at an early age and patients subsequently present at a later age with pathological fractures from mild to moderate trauma.8

In this article, a series of three cases of pycnodysostosis that presented to the dental hospital is described and their management discussed.

Case one

A 13-year-old female was referred to the Paediatric Department at Birmingham Dental Hospital. She was accompanied by her mother and sister who also had pycnodysostosis. The patient's primary complaint was the crowding of her teeth and she felt her anterior teeth were in the wrong place. As a result of the pycnodysostosis, she had fractured her arm as a baby, needed growth hormone periodically and also suffered with sleep apnoea for which she had her tonsils and adenoids removed and used a C-PAP machine.

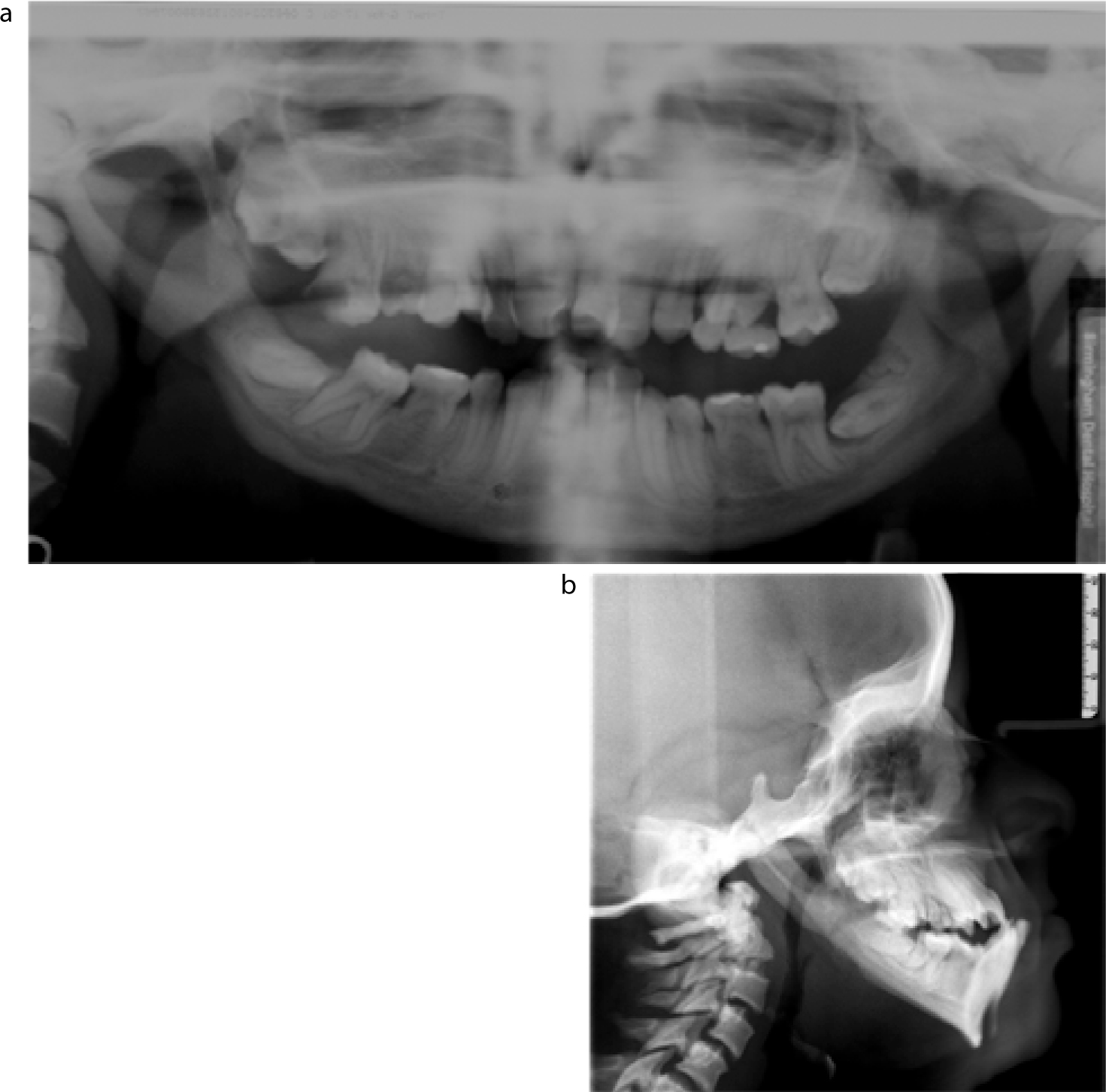

On clinical and radiographic examination, she presented with fair oral hygiene, mild generalized gingivitis, dental caries (UR6), dysmorphic teeth, retained lower deciduous second molars with missing lower second premolars, delayed eruption of second permanent molars, severe crowding and a Class III occlusion on a Class III skeletal base (Figures 1 and 2).

A specialist orthodontic opinion was sought from a consultant in the Orthodontic Department. At this stage, a plan was made to attempt upper arch alignment using fixed appliances and to review her in one year to monitor her mandibular growth. The UR6 was temporized in the clinic and the patient was referred back to her general dental practitioner for intensive oral hygiene instruction, regular fluoride varnish applications and definitive restoration of the UR6.

Case two

A 16-year-old female (sister to Case one) was also referred to the Paediatric Department at Birmingham Dental Hospital. This patient was concerned with the colour of her teeth. As a result of the pycnodysostosis, she had suffered several leg fractures and also needed growth hormone periodically. She had undergone a bone marrow transplant at the age of 2.

On clinical and radiographic examination, she had poor oral hygiene, mild generalized gingivitis, dysmorphic teeth, crowding, severe hypodontia (missing 7 premolars) and a Class III occlusion on a Class I skeletal pattern (Figure 3).

A specialist orthodontic opinion was sought from a consultant in the Orthodontic Department. The case was discussed with a craniofacial surgeon. It was felt that the risks of orthognathic surgery outweighed the benefits and that the patient should be treated with orthodontic alignment only accepting the Class III incisor relationship.

A provisional plan to align both arches and idealize space for replacement of one premolar in the lower right and lower left quadrants was made. The patient was referred to the joint orthodontic-restorative team to confirm this plan. She was also referred to her general dental practitioner for intensive oral hygiene instruction and regular fluoride varnish applications.

Case three

A 15-year-old female was referred to the Paediatric Department at Birmingham Dental Hospital. The patient was concerned with her bleeding gums. There was no other relevant medical history apart from pycnodysostosis.

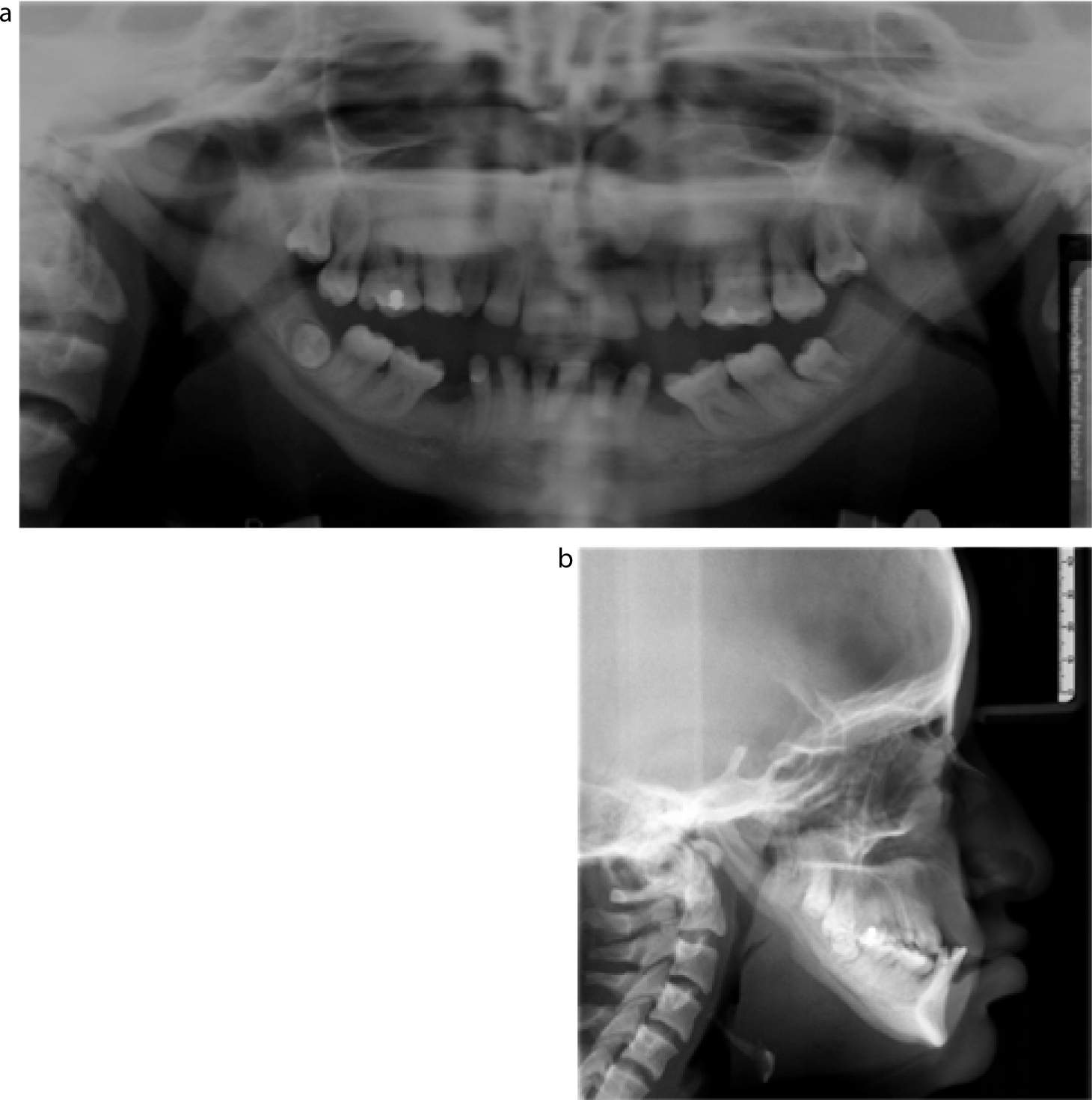

On clinical and radiographic examination, she had poor oral hygiene with generalized mild chronic periodontitis and dental caries (UL5). She had dysmorphic teeth with large pulp chambers and conical roots. Both upper second permanent molars were unerupted. She had a Class III occlusion on a Class III skeletal pattern (Figures 4 and 5).

On further discussion of this case with a consultant in Periodontology, a plan was made for the patient to have non-surgical periodontal treatment (root surface debridement) using local anaesthesia over two visits followed immediately by a course of broad spectrum systemic antibiotics. This would be supplemented with intensive oral hygiene instruction. No orthodontic intervention would be considered until the patient could demonstrate a good standard of oral hygiene.

Discussion

The three cases discussed all presented with general and craniofacial features consistent with pycnodysostosis: short stature, evidence of bone fragility, absent/obtuse mandibular gonial angle, hypoplastic mandible and midface, and bossing of various cranial bones.

Pycnodysostosis is not a life-threatening condition and therefore symptoms are treated as and when they arise.13 Despite this, complications that can arise from surgical interventions, such as dental extractions and orthognathic surgery, carry a high morbidity.

One of these complications is osteomyelitis secondary to surgical trauma, such as dental extraction or orthognathic surgery. Owing to the impaired vascularity of the bone in these cases, its healing potential is greatly reduced. Although there have been no reported cases of osteomyelitis in children with this condition after extraction of a malpositioned non-infected tooth, the potential for this increases with age. Another complication in these patients is the risk of mandibular fracture during dental extraction due to increased bone fragility. This has been reported following extraction of permanent teeth in adults.16

One of the presenting features of pycnodysostosis is a hypoplastic maxilla and mandible which often results in dental crowding that can make achieving good oral hygiene challenging. Consequently, patients with pycnodysostosis are at a high risk of developing dental caries and periodontal disease, as well as impacted teeth. They therefore have an increased probability of suffering from the aforementioned complications due to the possibility of requiring surgical intervention. With this in mind, the importance of early specialist referral and instilling an intensive preventive regimen cannot be stressed enough. The risk of post-extraction osteomyelitis can be reduced with the use of an atraumatic and aseptic technique.

There have been very few cases where orthodontic management and orthognathic surgery have been reported. Some authors suggest planned, serial extractions to relieve crowding from an early age.6,14 However, one of these authors also reported difficulty with the use of removable appliances in helping to correct the patient's malocclusion. Orthodontic treatment is reliant on bone remodelling via osteoclastic activity. Hence the underlying defect in this mechanism makes orthodontic treatment unpredictable and difficult. Successful orthognathic surgery and maxillary distraction have been reported despite the risk of osteomyelitis, non-union, poor bone healing and bone fractures.11,17,18

Conclusion

These cases highlight the need for early specialist referral, an intensive preventive regimen and multidisciplinary input in patients with pycnodysostosis. The oral health outcomes for these patients can be vastly improved by following these principles. Furthermore, this rare condition may not have been previously diagnosed and may present primarily to a dentist with delayed exfoliation and eruption of teeth. It is therefore important for the general dental practitioner to be aware of this disorder and the potential complications that may arise as a result of dental treatment.