References

Can we justify combined orthodontic and orthognathic surgery treatment?

From Volume 11, Issue 3, July 2018 | Pages 100-104

Article

Orthognathic surgery in combination with orthodontic treatment requires a significant time commitment from both the surgeon and orthodontist, constituting 7% of patients' treatment by UK-based Orthodontic Consultants.1 Consequently, it also commands a great deal of funding from the NHS and, in a climate of spending cuts across our health service, a need has arisen to justify service provision.

Orthognathic surgery is defined as surgical treatment of various dentalfacial deformities and anomalies. Included in this group are certain syndromes and conditions including:

These patients often have associated malocclusions that are not amenable to orthodontic treatment alone and thus need a combined approach involving both orthodontic therapy and jaw surgery.

It is important that such patients are offered treatment, as there is a possibility of functional problems, aesthetic concerns, as well as psychological and social integration issues. The impact of orthognathic surgery on quality of life has been demonstrated, as has the quality-adjusted life year (QALY). QALY is a measurement of the burden of disease and incorporates both the quality and quantity of life lived. In addition to this it assesses the value of any medical intervention.2 This is often increased further as most patients undergoing such treatment are young and will therefore benefit from life-long effects of intervention.3

In 2007, Hunt and Cunningham undertook a systematic review, which showed that orthognathic patients experienced psychological benefits, including improved self-confidence, body and facial image and social adjustment, as a result of treatment.4 A more recent systematic review by Alanko et al also noted that orthognathic treatment resulted in improvements in well-being.5 Although there are aesthetic concerns that motivate patients to undergo such surgery, some studies found that functional problems were the primary factor in motivating treatment.

Indices are used to facilitate better understanding of aetiology, risk, prognosis and outcome of a treatment, as well as serving as a tool to determine prevalence. Increasingly, indices are implemented to help with planning and projection of publicly funded services, thus prioritizing treatment to those that both need it and are likely to benefit from treatment. Currently, the most commonly used indices in Orthodontics are the IOTN, ICON and PAR. In addition to this, many orthodontists and maxillofacial surgeons will be aware of a number of indices for assessing the severity of malocclusions associated with cleft lip and palate patients, namely; the GOSLON yardstick, Five-Year-Old, Bauru-Bilateral Cleft Lip and Palate yardstick, Huddart-Bodenham, Modified Huddart-Bodenham, EUROCRAN yardstick, and GOAL yardstick.6

Essentially, five types of indices exist:

Currently, the IOTN exists in orthodontics to limit access to NHS Orthodontics and prioritize treatment provision to patients most likely to benefit from orthodontic intervention. The IOTN was developed by Brook and Shaw7 to assess treatment needs. They also developed the Peer Assessment rating (PAR) to evaluate treatment outcome. Shaw et al stated that using such indices would offer a number of advantages, such as uniformity in prescribing patterns, safeguards for the patient, patient counselling, as well as monitoring and promoting standards.8

This index ranks malocclusions in terms of the significance of various occlusal traits and assigns them a grade based on the single worst feature, with the aim of identifying those most likely to benefit from treatment. This index comprises two parts:

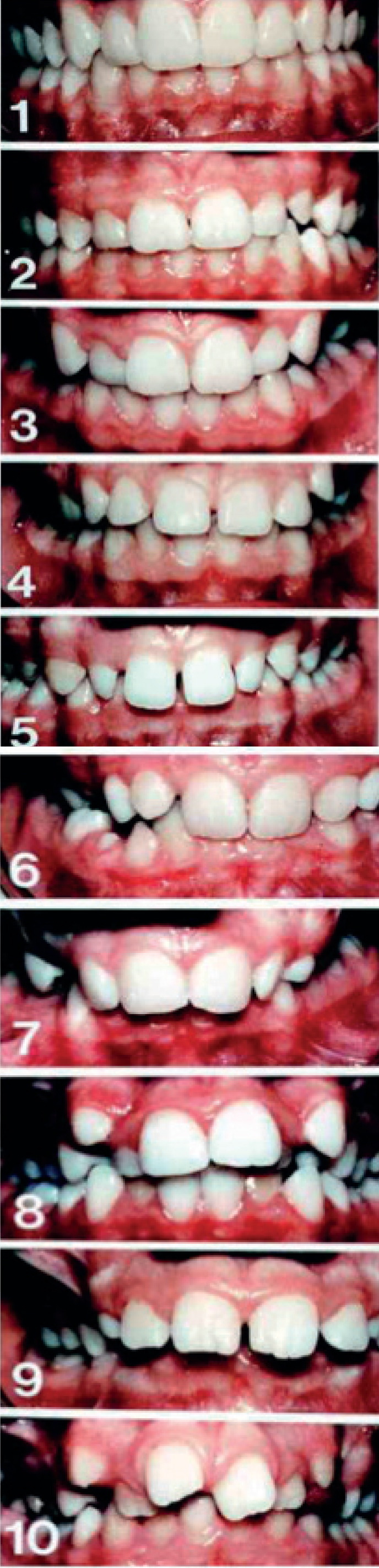

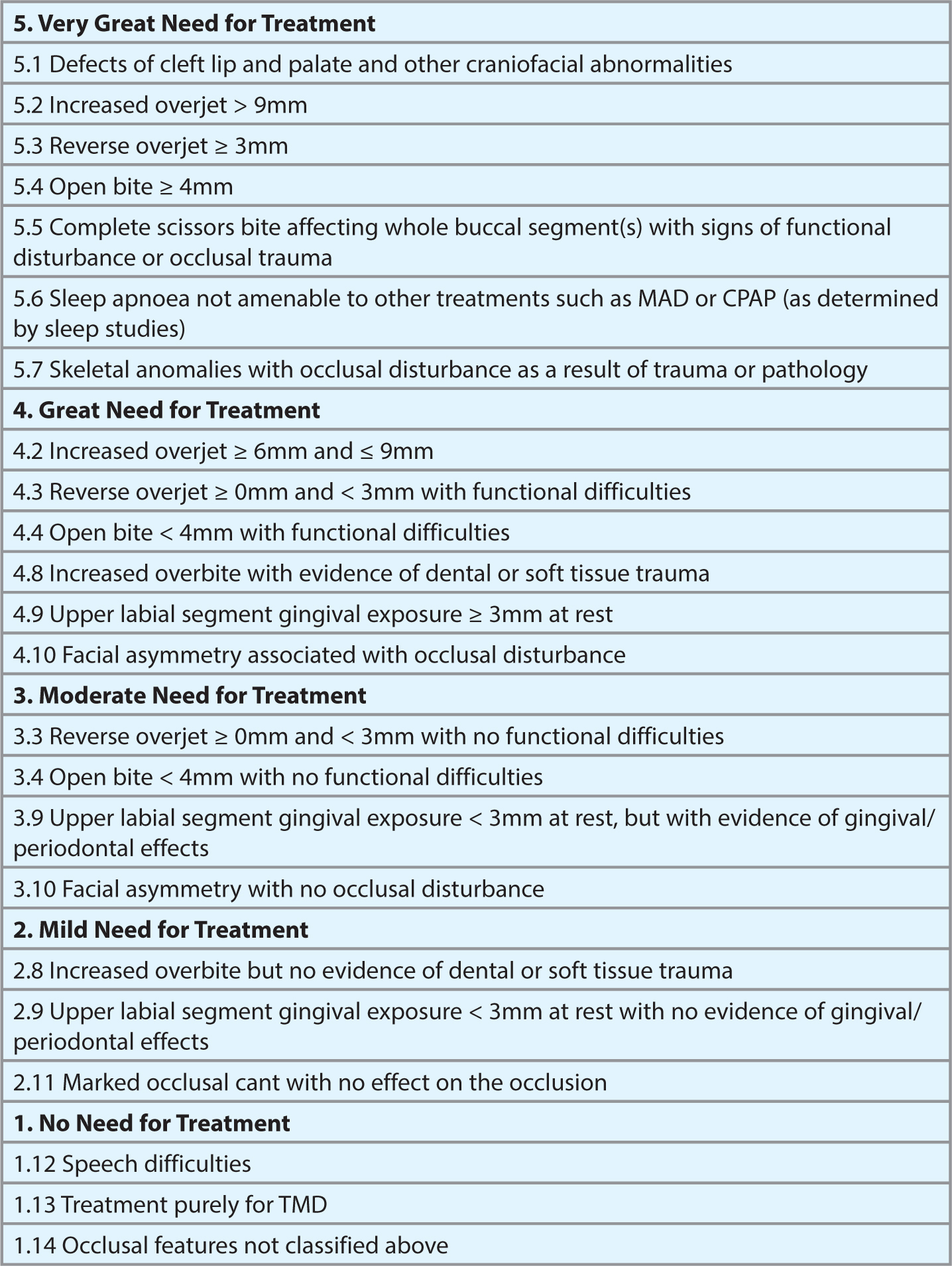

The IOTN DHC is based on a 5-point scale grading malocclusions from 1 to 5 based on various occlusal features, with 1 being no need, 3 being borderline and 4 and 5 great need for treatment. The IOTN AC is a series of 10 graded photographs of various malocclusions of various aesthetic compromises which are best matched by both the clinician and patient to the patient's teeth purely in terms of aesthetics. Currently, patients with an IOTN grade of 4 or 5, or with a grade 3 and Aesthetic Component grade above 6, are eligible for treatment under the NHS. For combined surgical and orthodontic patients, however, there is no indication for functional need for treatment, thus patients requiring orthodontic and surgical intervention may not actually score high enough on the IOTN to qualify for treatment.

With such shortfalls in mind, an index based on the IOTN has been developed known as the Index of Orthognathic Functional Treatment Need (IOFTN).10 The IOFTN applies to patients with malocclusions that are not amenable to orthodontic treatment alone due to skeletal deformity and prioritizes them in accordance to treatment need. Furthermore, it is intended for use in conjunction with psychological and clinical indicators as it only relates to the functional need for treatment.2 As with the IOTN DHC, the IOFTN is based on a 5-point scale. When designing the IOFTN, four experienced consultant orthodontists used the IOTN DHC as a basis for developing this new index.8

It is hoped that the use of this index will prevent orthognathic surgery being classified as a low priority treatment and have funding withdrawn. Furthermore, this index will help to provide treatment for some skeletal deformities that do not score high enough on the IOTN currently to qualify for treatment.

Aims

The aim of this study was to assess whether our cohort of patients undergoing combined orthodontic and orthognathic surgery treatment would have qualified for orthognathic surgery according to the new index produced, the Index of Orthognathic Functional Treatment Need (IOFTN). Furthermore, this study is to assess its ease of use, the difference between the IOTN and the IOFTN and whether this new Index is worth introducing to our daily practice in hospital orthodontic departments. Additionally, the study was:

Materials and methods

This was a retrospective study of 44 patients who underwent, and are currently undergoing, combined orthodontic and orthognathic treatment in Lanarkshire. Each patient's IOTN was taken from his/her initial orthodontic assessment and, using the criteria set out with the IOFTN, an IOFTN grade was assigned to each patient according to the criteria outlined in Figure 3.

Results

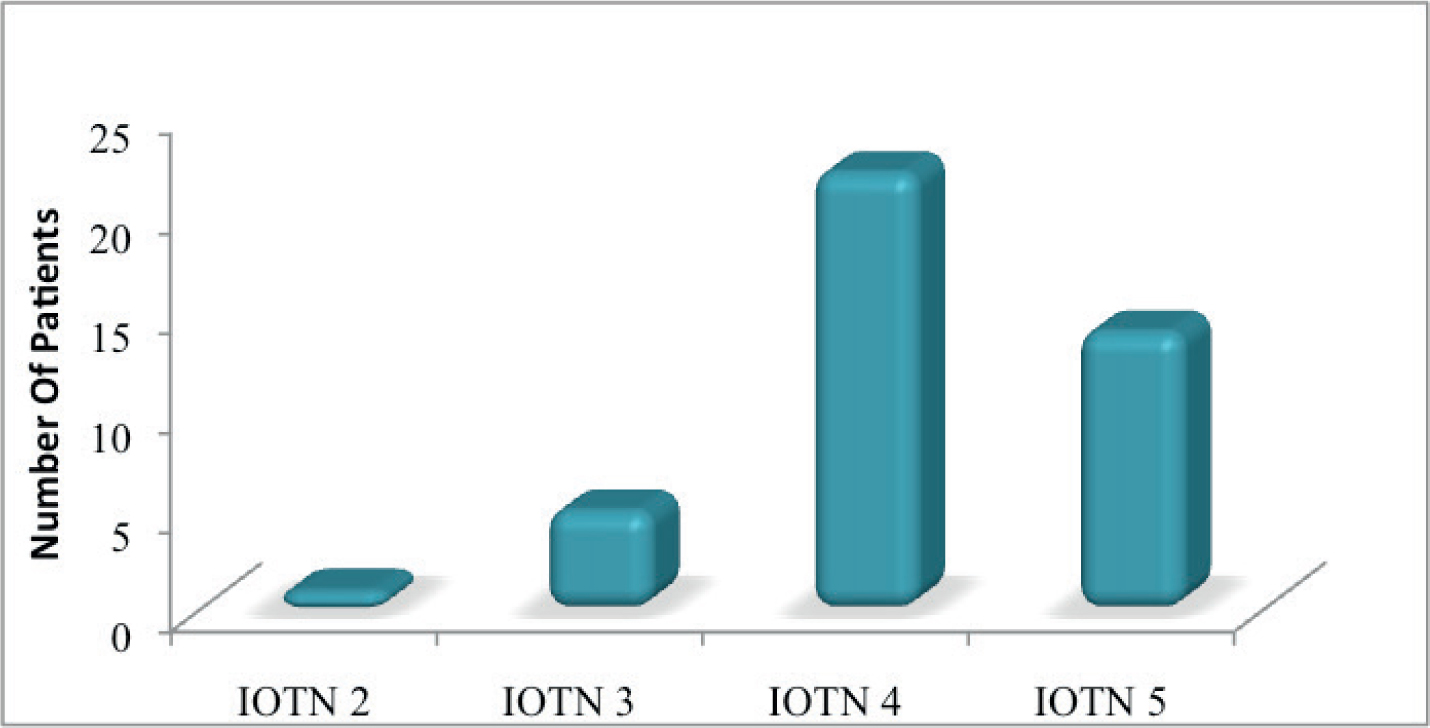

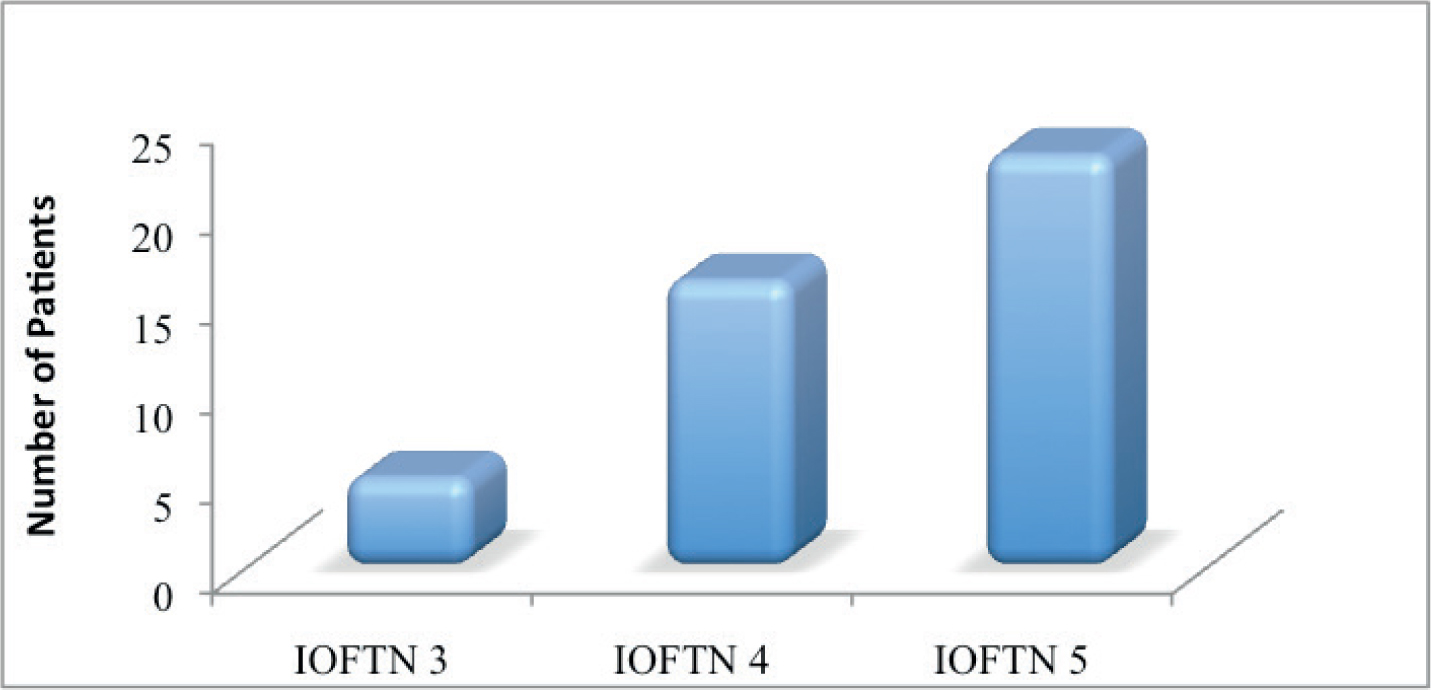

In total, 44 patients were assessed, 24 males and 20 females. The majority of patients (61%) were skeletal Class III, 36% were Class II (27% Class II division 1 and 9% Class II division 2), and 2% Class I (Figure 4). Using the IOTN, 90% of patients were in a high need for treatment, changing to 98% using the IOFTN (Figures 5 and 6). Nine patients' treatment need increased when using the IOFTN, although this only moved them from a Category 4 to 5, thus no real difference in need as both grades would qualify. For two patients, however, the IOFTN placed the patient in a greater treatment need category from a borderline need, however, the aesthetic component would have justified intervention anyway.

Discussion

It would be unrealistic to expect a single index to fit all the patients that we treat, therefore this new index should be welcomed as another tool to assess our patients. This study has shown that the majority of our patients are already high priority. However, using the IOFTN confirms this as a means of identifying such need to funding bodies. Furthermore, as the IOFTN is very similar in structure to the IOTN, those familiar with using the IOTN will find the IOFTN an easy and natural process.

It is surprising, however, that orthognathic surgery is under scrutiny and it is at risk of funding being cut, or even stopped in some regions. It has been shown that orthognathic surgery is in fact very good value for money, especially when compared to more common procedures, such as knee and hip replacements. Orthognathic surgery is said to improve quality of life greatly as there is a strong correlation with facial deformity and psychological and psychosocial problems which have been shown to have improved following orthognathic surgery. To class such treatment as purely aesthetic surgery is also unrealistic, as many of these patients have associated occlusions that impact upon function, leading to problems with mastication and even sleep apnoea.

This also brings about the question as to whether we truly have a National Health Service if such regional discrepancies exist across the country between Health Boards.

Conclusion

These results show that, in NHS Lanarkshire, those patients receiving orthognathic surgery can be classified as a high need for treatment according to the IOFTN. This helps to justify the service and helps with maintaining funding in this area. As this new index is being introduced into England, it is likely that it will travel north of the border and affect Scotland too.

As the results show, the need for treatment is not greatly different when using either index. However, the main difference exists for this cohort of patients in that it is specifically designed for those undergoing orthodontic treatment in combination with orthognathic surgery, something that the IOTN was not intended to incorporate. This index is more likely to stand the test of time as it does not greatly change need for treatment but is more specific when justifying it, an element that is likely to be of benefit when incorporating it into our publicly funded health service.

The index is likely to be welcomed, as it is familiar, due to its similarity with the IOTN, and simple to use. It is beneficial for audit purposes and, furthermore, classifies the patients who we deem are in need of surgical intervention but score low on the IOTN and thus do not technically qualify for combined treatment.

The IOFTN should become part of each assessment form, thus making the transition simple when or if it is introduced. Early adoption of this procedure would help identify any pitfalls with this index, which could potentially be rectified prior to its widespread introduction. Furthermore, as this is true combined care treatment, the IOTN (both DHC and AC) should still be implemented as these patients often have a number of treatment options and do not always wish to proceed with the full treatment package, thus comprehensive records from both specialties are required.

Currently, courses exist for calibrating operators in the use of the IOTN to ensure consistency. These, however, do not exist for the use of the IOFTN. Organizing some form of calibration would give greater validity and would enable objective comparisons across the UK. The study published for the IOFTN showed very good intra-examiner agreement and good validity, thus one would expect a calibration course or workshop would be beneficial to both orthodontists and surgeons.6