Patient referrals

There were significant variations in the number of referrals for the three years of the evaluation. The 2006 data may have been influenced by the closure of the waiting lists in primary care in 2005, causing a backlog of referrals. In addition, the recruitment of overseas dentists to improve access to NHS dentistry may have influenced referrals, combined with an unfamiliarity with occlusal indices and a lack of awareness of the process of prioritization in the UK. Training events were held on the use of IOTN in 2008 and this may have influenced the decrease in referrals in 2008–2009. Referrals from non-primary care sources and transfer cases from the mainland accounted for a very small proportion of patients seen. This area needs further investigation as funding should be calculated to include transfer cases and secondary care referrals in a merged service.

There are a number of factors which may influence orthodontic referrals specific to the Isle of Wight. Historically, the growth of orthodontic manpower on the IOW does not mirror the dramatic growth in the local population since 1999.14 Although the population in the United Kingdom is predicted to grow, the 7–20 year-old cohort will significantly decrease on a short-term basis, reflecting the low fertility rates from the late 1980s to early 2000.12 This potential reduction in the orthodontic referral cohort should be considered to enable better planning and use of manpower resources.

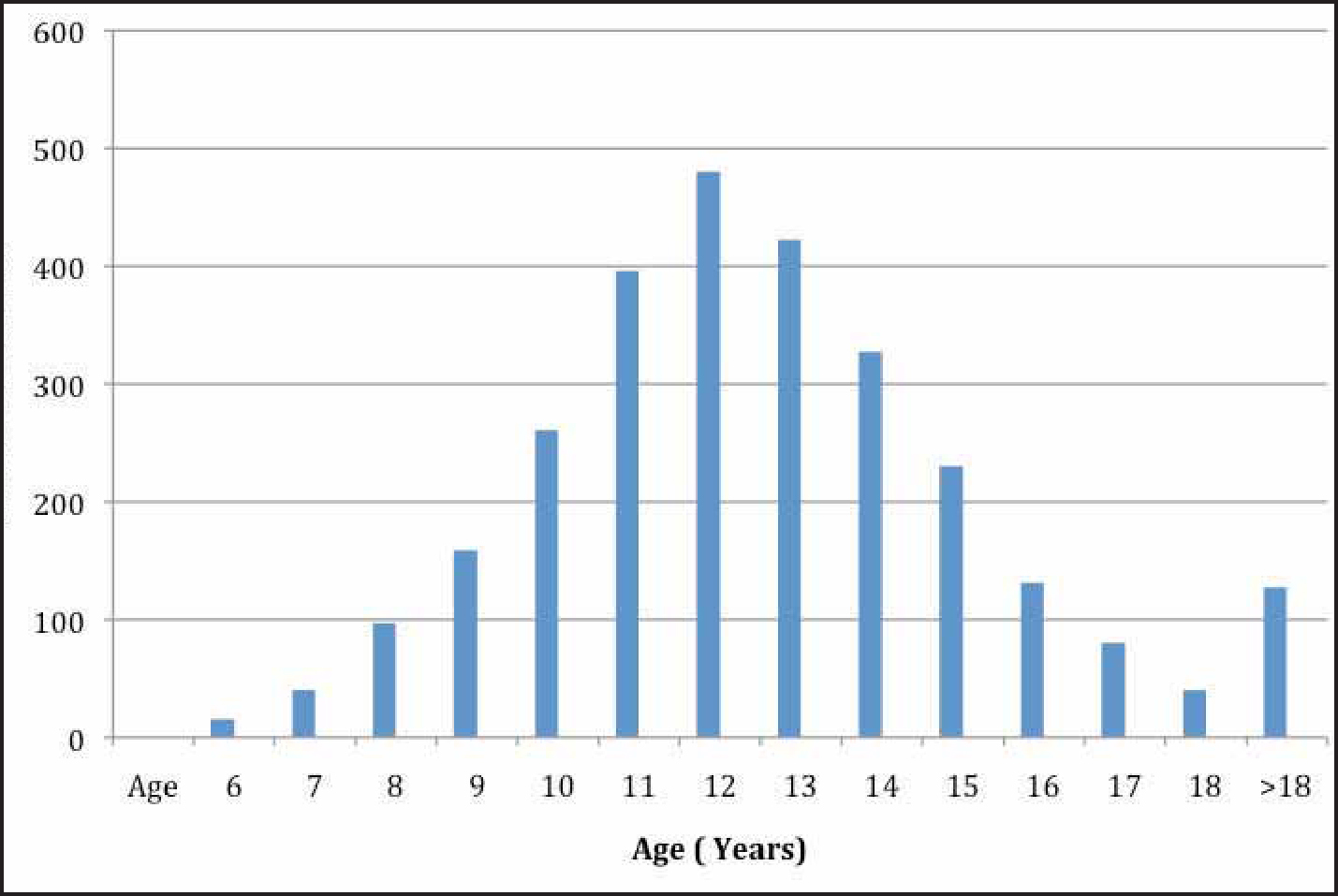

From the data collected during the study period, more females (54%) than males (46%) were referred for orthodontic care. This has been previously reported in other UK studies.8 However, in 2001, Üçüncü and Ertugay found no statistically significant difference in IOTN between the sexes15 and the 2003 Children's Dental Health Survey6 reported the need for treatment to be the same for boys and girls aged 12 years. The difference in demand between boys and girls could be a reflection of the standards of aesthetics and beauty, which are more clearly delineated for females.16 Shaw et al17 found twice as many females as males receiving orthodontic treatment and that females considered they were of below average attractiveness. However, the lack of evidence relating to sex and gender differences in oral health has been highlighted.18

As can be seen from the referral data, the peak referral age was 12 years. A 1991 analysis of Dental Practice Board records showed that the mean age at commencement of treatment in the General Dental Service in England and Wales was 12.7 years.19 A comparison of these data suggests that patients are being referred later to the IOWOS and, therefore, the mean age at commencement of treatment will be greater than 12.7 years. However, there has been considerable reorganization of orthodontic services nationally since 1991. The introduction of the specialist list leading to the provision of more complex dual arch fixed appliance therapy to improve standards, a reduction in early treatments in the mixed dentition and a reduction in the number of general dentists providing interceptive care can all have an impact on the age of referral. No data has been collected on the commencement of treatment for IOWOS, therefore a direct comparison cannot be made. This information is important as the correct timing of referral and the start of treatment could reduce early referrals, ultimately improving the patient pathway. The peak referral age of 12 for the IOW is not unexpected as most children are in the late mixed dentition or permanent dentition at this stage of development. A recent pilot central referral triage in Southampton, Hampshire and Portsmouth PCT areas, in response to the IOW MCN, found a comparable age distribution.20 The development of an occlusal index has standardized the approach to assessing whether referrals for orthodontic care are appropriate. The lack of integration of primary and secondary care has led to a number of audits to measure the appropriateness of referrals, but with limited success. O'Brien et al21 found many orthodontic referrals were unnecessary. From the IOW referral data, it has been possible to assess the IOTN of the referred population after referral and triage for the 11–18 year-old cohort. From these data, the referral pattern by dentists, ‘the major gatekeepers’ to the service, has demonstrated that, in accordance with referral guidelines, 88% of patients were categorized IOTN 5, 4 and 3/SCAN 6 or higher. It is possible to make comparisons with figures described by Robinson et al in the Orthodontic Workforce Survey.6 The survey of orthodontic practitioners in Hampshire and the Isle of Wight showed that the estimation of their time spent treating IOTN 4 and 5 was 78%. The IOW referral patterns confirm that 80% of referrals were categorized as IOTN 4 and 5, ie high need, and indicates appropriate referral patterns; 8.5% were IOTN 3/SCAN 6 or higher and reflected moderate need, and inappropriate or unnecessary referrals accounted for 11.8% of referrals. Other studies have analysed the Dental Health Component (DHC) of IOTN in a referred population of 11–14 year-olds.15 In these studies, moderate need was described as DHC 3. However, in the IOWOS sample of 11–18 year-olds, only IOTN 3/SCAN 6 or higher was deemed to represent moderate need. This might explain the difference in the IOWOS results compared to previous studies. The results for those patients assessed as being in high need (IOTN 4 and 5) were comparable to the results found in previous studies.

Recent studies have highlighted the need to provide more support and education for dentists concerning the use of IOTN22 and further training has been planned in this area. The National Health Service Business Services Authority routinely report to PCTs about the percentage of patients receiving treatment with an IOTN 3/SCAN 6 or higher. Whilst it is acknowledged that a few patients may have been transferred from the pre-2006 triage system, it is important that the decision to treat these mild cases within the NHS is justified. The data from the IOW demonstrates that only 11.8% of 11–18 year-olds were included in this category. There are currently no data on how many of these patients receive NHS care or how many were treated under private contract in general practice.