Abstract

The orthodontist plays a significant role in the management of children with cleft lip and palate. This article summarizes the key stages of input and some of the challenges that may be encountered.

From Volume 6, Issue 4, October 2013 | Pages 102-108

The orthodontist plays a significant role in the management of children with cleft lip and palate. This article summarizes the key stages of input and some of the challenges that may be encountered.

In this article we intend to concentrate on the orthodontist's role within the multidisciplinary clefts team and the dental team. The orthodontist's aim is to provide a dentition that functions well and is capable of a life-time's maintenance by routine oral hygiene and dental care.1 Some aspects of the cleft orthodontist's role will be covered in other articles within this series, including his/her role within alveolar bone grafting preparation and preparing patients for orthognathic surgery.

Patients who present with a cleft affecting the alveolus may often have duplication of tooth types on either side of the cleft, malformed roots and/or crowns, enamel hypoplasia, absence or ectopia of teeth. There is evidence that patients with cleft anomalies may have missing or aberrant teeth distant from the cleft in either jaw. Hypodontia in patients with cleft lip and palate has a higher prevalence compared to the normal population in the UK.2 Combined with dental anomalies, patients with clefts have a higher incidence of dental caries than the non-cleft population,3,4,5,6 complicating the orthodontic treatment planning decision.

With the increased caries incidence, prevalence of dental anomalies, unfavourable growth patterns and the requirement for grafting of the alveolus, these patients present a significant challenge to the dental team.

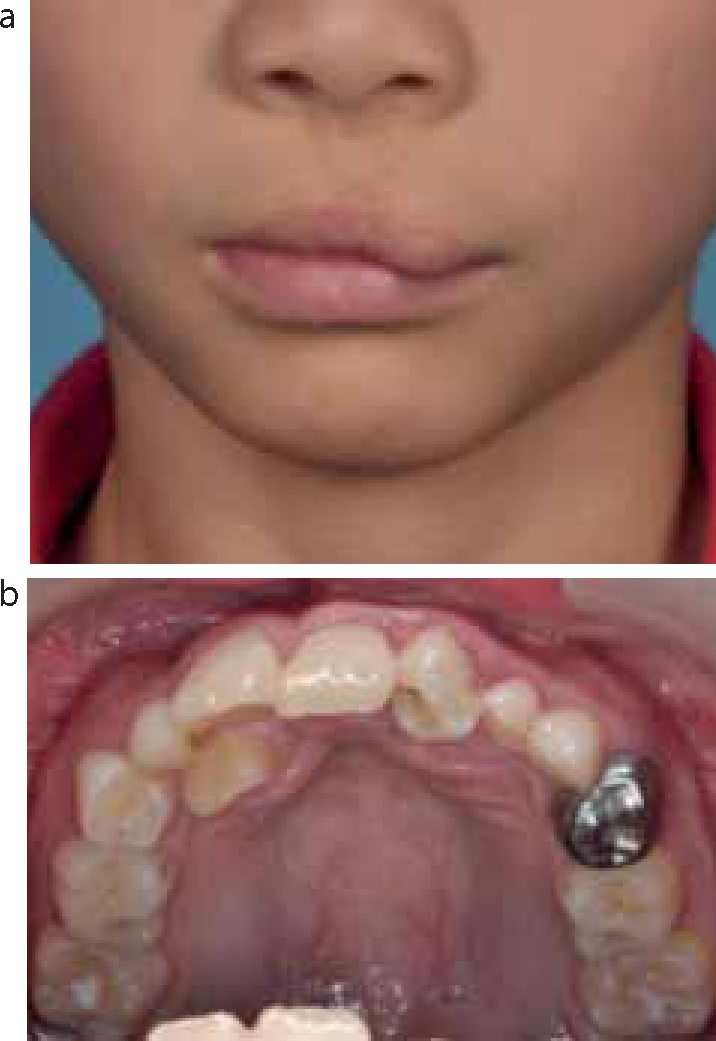

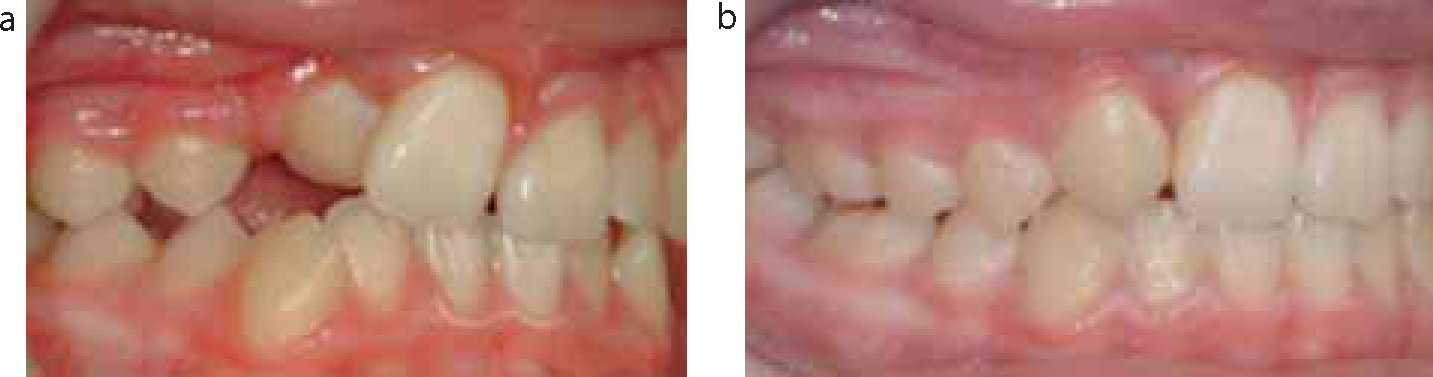

For much of this article we will be discussing orthodontic input in relation to children with cleft lip and palate. Children, however, that have a cleft palate only (40% of UK cleft population) have a tendency towards bi-maxillary retrusion, crowding and Class II division 2 malocclusion and an increased frequency of other associated dental anomalies, including hypodontia.7 As the cleft does not involve the tooth-bearing area, the impact of the cleft in the orthodontic management is limited (Figure 1a, b).

Cleft lip may or may not have an impact on the tooth-bearing region adjacent to it. Its impact on the alveolus may vary from no effect to a significant notch. With or without an alveolar defect, the impact on the developing teeth associated is variable (Figure 2).

When the notch is significant, there will be major implications for the orthodontist in relation to tooth movement, necessitating bone grafting if roots are to be moved into this region. Radiographic screening as the incisors are erupting is routine with or without three-dimensional scanning to confirm the defect extent.

Traditionally, the orthodontist has five key periods of input for a child with cleft lip and palate (Table 1). Some of these aspects are covered in separate articles within this series (Primary Surgery, Alveolar Bone Grafting and Orthognathic Management). Despite these discrete times for active intervention, routine recall for monitoring dental health and facial growth continues to occur within the dental team.

| Orthodontic Procedure/Input | Timing |

|---|---|

| 1. Pre-surgical orthopaedics/strapping | Primary surgery (<6 months) |

| 2. Pre-bone graft orthodontics | 7–10 yrs |

| 3. Orthodontic alignment/definitive input | 11–13 yrs |

| 4. Pre-orthognathic decompensation | End of growth |

| 5. Orthodontic audit | 5, 10, 15, >18yrs + |

Children with cleft lip and palate have been shown to undergo a significant amount of orthodontic input up until the age of 17 years.8 Modern orthodontic management looks to reduce the burden of care for the child, keeping the duration of any intervention to a minimum.

This aspect of orthodontics is principally covered in the article on Primary Surgery. Pre-surgical orthopaedics has had phases of popularity, historically, in an attempt to improve the apposition of the bony and soft tissue segments, therefore aiding the surgeon at the time of primary surgery. Various techniques exist with or without lip-strapping. The removable plates utilized can be broadly classified as active or passive plates, depending on whether an active force is applied to the segments or whether the plate merely sits passively, preventing the tongue from sitting between them.

Claims to improve feeding, weight gain, growth, speech and time for surgery in unilateral cleft lip and palates, have been largely disproved within the ‘Dutchcleft’ project.9 Similarly, little benefit has been seen in cases with bilateral cleft lip and palate in a retrospective evaluation.10

These appliances have been shown to increase the burden of care for the patient significantly11 and have generally fallen out of favour within the UK, except for isolated clinical reasons; usually bilateral cleft lip and palate patients where the pre-maxillary segment is trapped anteriorly.

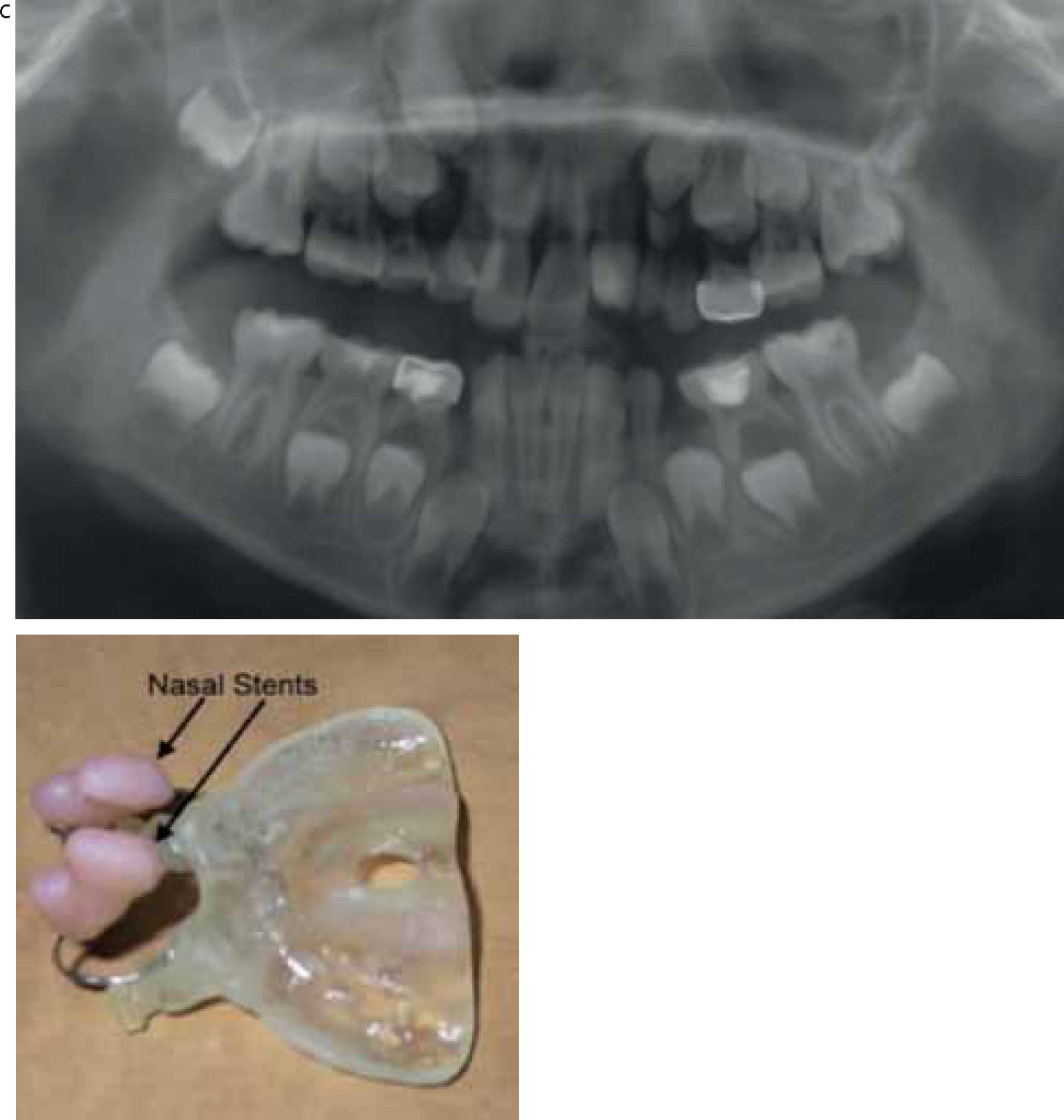

In an attempt to improve nasal form post-primary surgery, a modification of pre-surgical orthopaedics, naso-alveolar molding, has been proposed.12 Nasal stents attached to the plate (Figure 3) attempt to elevate the nasal rim, increasing its convexity and improving its form post-surgery. Despite a lack of good evidence to back up the claims, the results in the short term in relation to nasal form appear promising.13

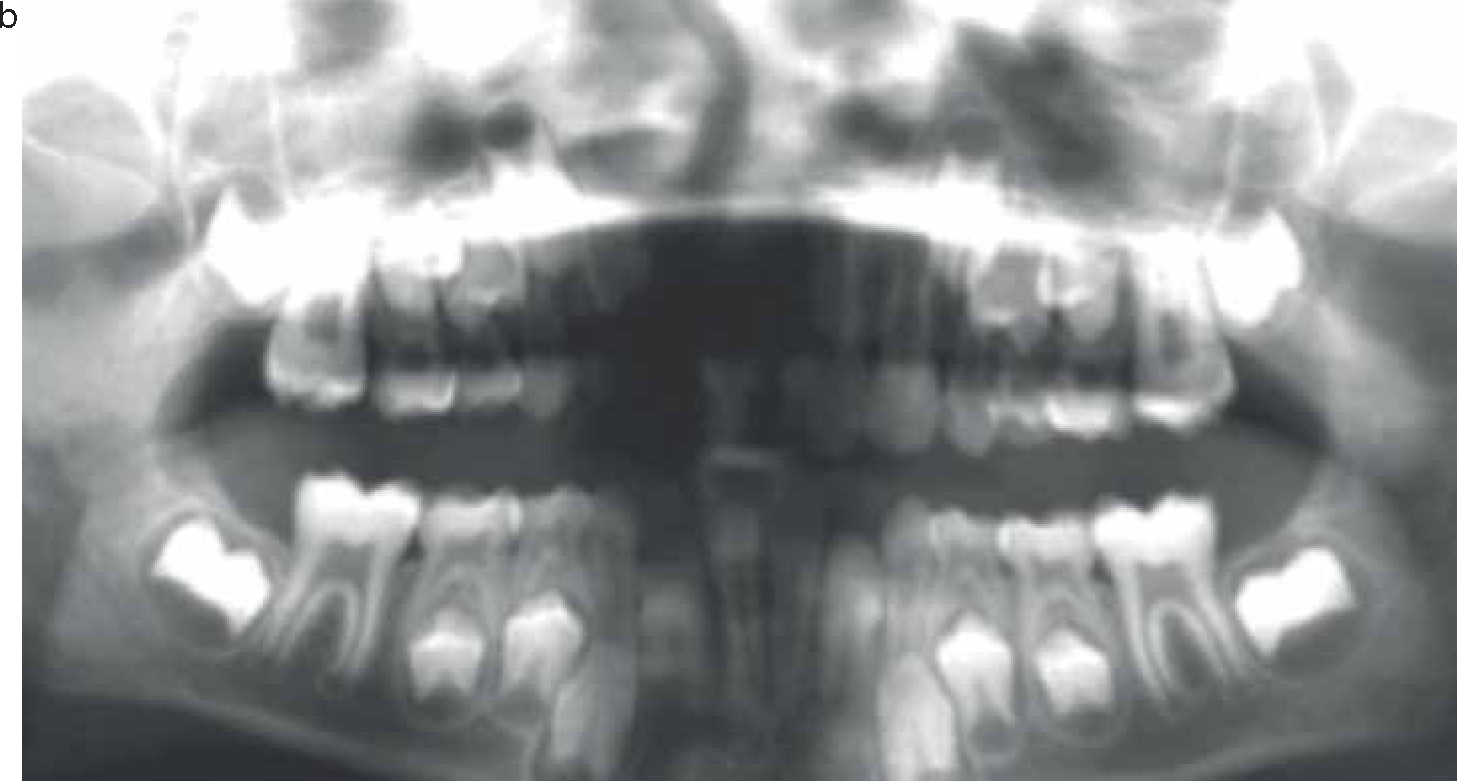

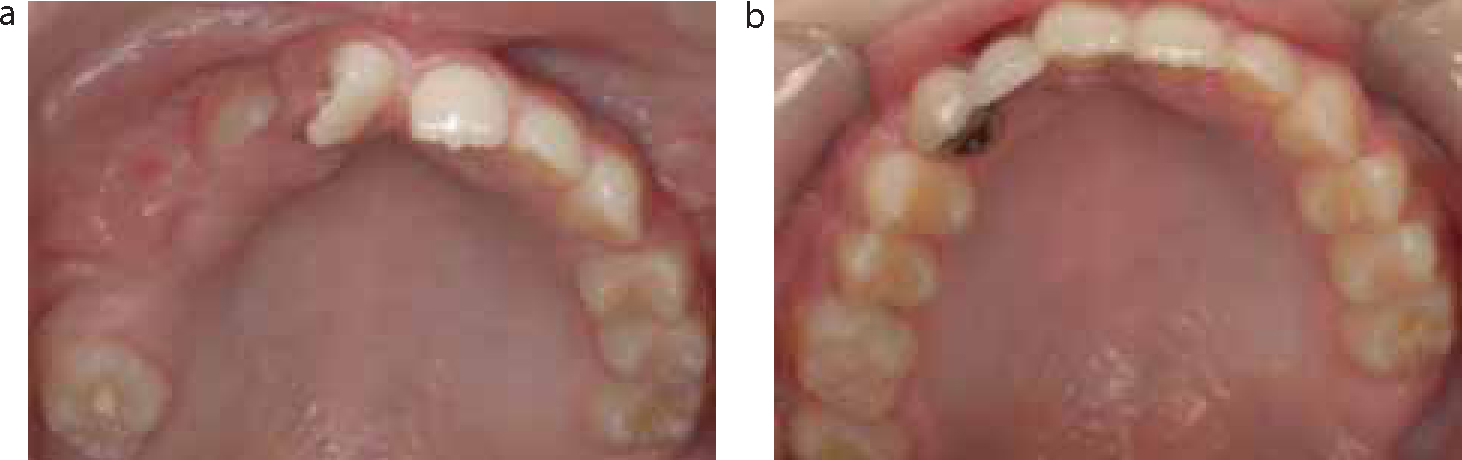

This aspect of orthodontic care is covered in the article on Alveolar Bone Grafting. The timing assessment is made around the age of 7 years, with clinical and radiological assessment. In patients with cleft lip and an associated impact on the alveolar ridge, this assessment may be supplemented by cone beam computer tomography (CBCT) to aid evaluation of the cleft extent (Figure 4). It is essential during assessment that there is confirmation that a tooth is available to erupt into the bone graft as otherwise the graft will largely disappear within three years of its placement.14

Orthodontic input is usually to aid access for the surgeon to the cleft site and anterior crossbite correction, if possible, without risking tooth vitality. Significant tooth movement, particularly of the anterior teeth, is generally avoided in teeth adjacent to the cleft site. Patients with bilateral cleft lip and palate require input in order to stabilize the pre-maxillary segment, which is often mobile and is usually achieved using fixed orthodontic appliances and a rigid archwire from the anterior teeth to the first molars (Figure 5).

Expansion can be a challenge in children so young and is usually carried out using a fixed quad helix type appliance and its duration is ideally kept to a minimum. Appliances covering the palate will need to be removed and replaced during surgery or replaced with something less obtrusive prior to surgery. This aids access to the cleft site for the surgeons and improves the likelihood of producing a watertight seal around the grafted bone. The appliances are generally kept in place for 4-6 months post graft at which point a radiological assessment is made of success and the orthodontic appliances are removed. The patient is then placed on recall to allow monitoring of the remaining permanent teeth, in particular the cleft canine that has an increased tendency to become impacted.

Orthodontics for patients with cleft lip and palate presents a number of challenges in comparison to conventional orthodontic treatment for a non-cleft population:

When the cleft involves the alveolus it is likely to result in a number of dental anomalies within or adjacent to the cleft site. These include:

The advent of alveolar bone grafting has transformed the orthodontic management of children with a cleft involving the alveolus and allows orthodontic space closure.14,15 It is generally felt that space closure is preferable to space opening and, in some ways, the space opening option removes the benefit of the graft itself, as a tooth within the graft is essential for its continued presence. The aesthetic concerns of asymmetric, high gingival margins associated with a canine substitution for a lateral incisor are generally unfounded owing to the relatively lower lip line associated with a repaired cleft of the lip (Figure 6). Aesthetics of the canine may also be improved with selective bleaching and modification (Figure 7).

In general terms, the growth of children with cleft lip and palate tends to show a Class III tendency; this is particularly noted in males.16 Cephalometric analysis shows a short retrusive maxilla and increased lower facial height. The aetiology of this growth pattern is complex, being a combination of an intrinsic growth pattern and the iatrogenic effect of surgery.

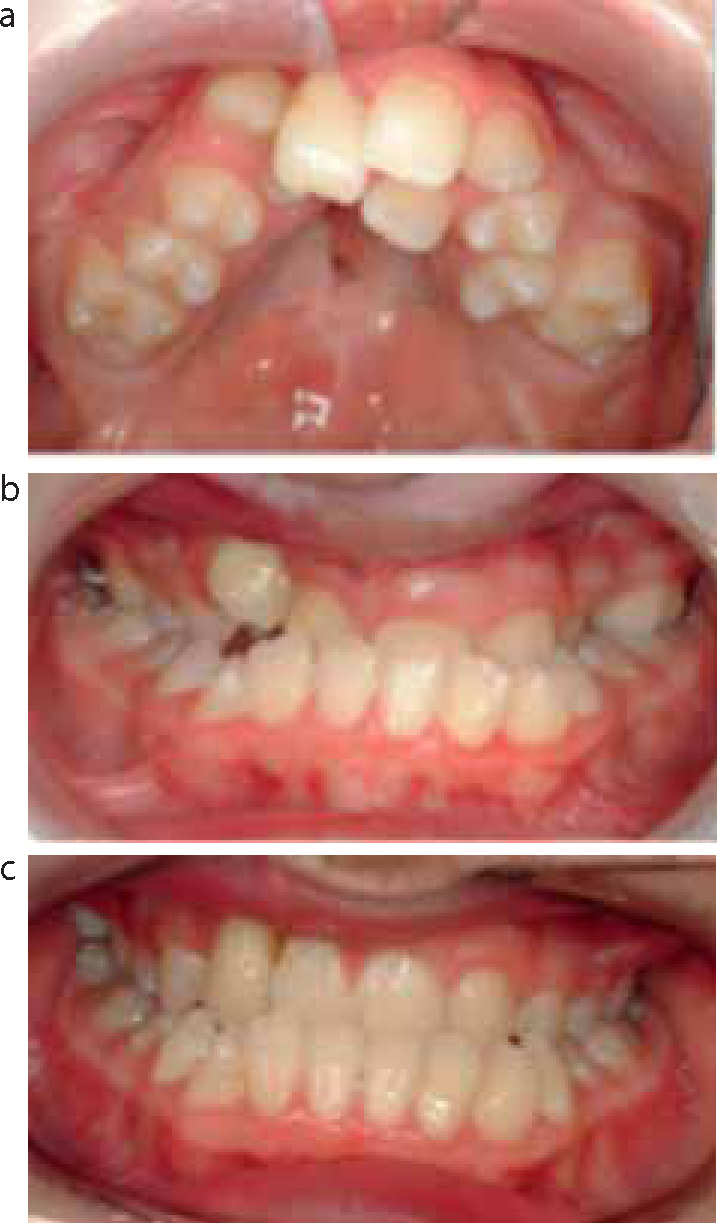

A decision needs to be made once the permanent teeth have erupted as to whether the teeth should be lined up on the dental bases accepting a Class III incisor position (Figure 8), or whether an attempt should be made to correct or camouflage the dental bases (Figure 9). The likelihood of whether orthognathic surgery may be considered in the future will need to be discussed with the patient/parents and team before any attempt is made to compensate/retrocline the lower incisors in an attempt to correct the incisor relationship.

Where orthognathic surgery is to be considered in the future, simple alignment of the upper arch over a limited duration, accepting or aligning the lower arch, may be the preferred option in early teens.

Where facial aesthetics are satisfactory and skeletal relationships allow, orthodontic camouflage may be considered with caution.

Alveolar bone grafting has transformed orthodontic options in patients with clefts involving the alveolus. Bone graft success rates in the UK are high,17 although rely on tooth eruption into the site for continued success. If a tooth erupts slightly distal to the site, bone loss on the mesial side of the tooth may preclude space closure without threatening the vitality of the tooth (Figure 10).

Tooth movements in the alignment of the dentition in patients with cleft lip and palate may be significant in distance and relapse potential. Teeth associated with the cleft are likely to erupt, be rotated and significantly displaced (Figure 11).

This results in challenges for long-term retention. Bonded retainers, particularly across the cleft site, are generally the retainer of choice (Figure 12), but are frequently combined with a removable type retainer, in the form of a pressure formed type with transverse strengthening, or a Hawley retainer in the upper arch.

This aspect is covered in the Orthognathic Management article within this series. The possibility of orthognathic surgery must, however, be considered before commencing orthodontic treatment for children in early adolescence, particularly where camouflage is considered. Reversing orthodontic compensation in late teens to allow an orthognathic approach can be time consuming and challenging.

The orthodontist and his team (therapist and appropriately trained nurse) play a key role in the collection of audit records within the cleft team. Study models and/or intra-oral photographs with overjet measure are considered an essential record for measuring growth as an outcome, using either five year18 and/or GOSLON indices.19 The assumption is made with both indices that the more unfavourable the occlusion, the more unfavourable the growth (Figure 13). The criticism is often made, however, that occlusion may not always relate to facial appearance.

Orthodontic audit records are taken at regular intervals, starting at age 5 years and throughout the child's development, with prescribed radiographs to assess dental development/growth and bone graft outcome. The measures have been used previously to assess the care throughout the UK.20 The recommendations for audit records within the UK are provided by the Craniofacial Society of Great Britain and outcomes stored on the CRANE database for England, Wales and Northern Ireland and the CLEFTSiS database for Scotland.

Currently, the commissioners of cleft services in England and Wales request both the orthodontic outcome, as measured using the PAR index,21 and alveolar bone graft outcome, as measured using the Kindelan Score22 on post-operative occlusal radiographs. The Orthodontic Specialist Interest Group of Craniofacial Society of GB & Ireland plays a lead role within its collection (Table 2).

| Age | Study Models | Photographs | Radiographs |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 yrs | X | X | |

| 10 yrs | X | X | Ant Occ (Post BG) |

| 15 yrs | Ant Occ (Canine eruption) | ||

| 18+ post treatment | X | X | Lat ceph |

The orthodontist's role within the cleft team is significant in terms of audit and orthodontic treatment intervention. Orthodontic input within the care pathway for children with cleft lip and palate is burdensome for both the child and parents. Current opinion suggests that episodes of care should be discrete and be of as limited duration as possible. The skills of the orthodontist are utilized to contribute to the end result in terms of primary surgery, alveolar bone grafting and orthognathic surgery. Conventional orthodontics for patients with cleft lip and palate is challenging and complicated by associated dental anomalies, unfavourable growth, bone grafting requirements and unfavourable tooth positions, resulting in retention issues.